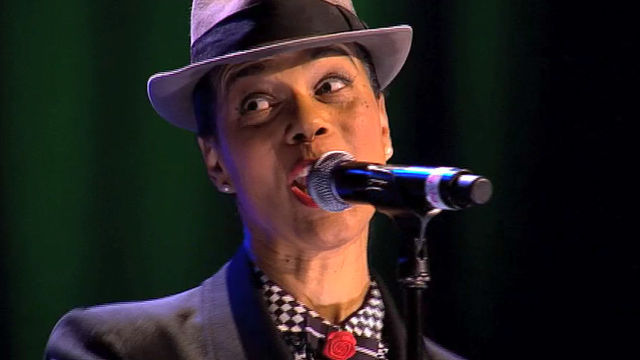

Pauline Black grew up in 1950s Britain as a mixed-race adopted child to white parents. In search of her identity, she found her way into the British Ska scene becoming the frontwoman of iconic band, The Selecter. Pride caught up with Pauline upon the release of her autobiography, ‘Black By Design’ to discuss her life less ordinary…

Firstly I’d just like to talk a bit about your upbringing. From your book, and what you’ve said in interviews, your childhood was quite challenging. You grew up in 1950s/60s Essex being an adopted, mixed-race child to white parents. How much of your upbringing has shaped you into who you are today?

Life is difficult for any mixed race child in this country, especially growing up in 1950s Essex. I grew up in a white working class family and the views they held wouldn’t be acceptable these days. It was quite hard for me at 4 years old to find out I was adopted, that I was an ‘other’ that I had an African father. It was quite hard for me to be singled out as ‘different’ and my parents did it because I was going off to school but it was quite brutal for it to be done in that way. It made me distrustful of adults in a way, they couldn’t be relied upon to tell the truth.

I imagine that distrust followed you through your adult life…

Yes. It made me quite introverted when I was young.

Would you say that the music became a form of escapism for you? A means to find yourself. When did you decide that was something you wanted to do?

I was quite old actually when I decided I wanted to pursue that. I was fairly introverted during my teenage years but had a hankering after reading quite a lot of science fiction- John Wyndham in particular, and I decided I wanted to be a biochemist. God knows why! I can’t remember which book, but one of the female protagonists was a biochemist and I thought it sounded quite cool. I thought “I want to be one of those!” I ended up at the Polytechnic in Coventry. I still wasn’t a part of music apart from listening to it. At that time there was a lot of Motown, Soul, and slogans around like ‘Black is Beautiful’ and then wonderful artists like Aretha Franklin walking down the street looking sexy and beautiful and it was all so great you didn’t feel like you needed anything else. All that stuff was fermenting in my mind for when I did actually start making music, so I had things I wanted to say. I wasn’t particularly content with just covering other people’s songs- though I did cover a few Joan Armatrading songs and a few Joni Mitchell songs because that was the only role model I really had at the time. That’s how I came to music. I was a singer-songwriter around Coventry until I was offered about £10 for ten songs and I met a politics student at Warwick University who said “You should come and write with me!” and so I went. I got an education in reggae music and moved on from there.

When you started appearing as an artist, you joined the Ska scene which at the time was known for featuring quite diverse line ups of artists. Was that an attraction for you?

That was the total attraction. It was a movement. It came with a whole ethos anti-racism and sexism. Everyone knew exactly when they got on stage, what they were up against.

How important was it being part of a label like 2Tone?

Very important. 2Tone was an independent record label. Yes, it was under a major record company but we could make the decisions about what records went out on it. For instance if we wanted to give £1000 to a new band with the same ideals as us like The Beat or The Bodysnatchers at that time, we could do that and they could come in and produce for us. The albums created on 2Tone were almost like mini collectors items because the iconography was so good and the messages registered with people. You still had black people being beaten up and harassed in 1979 and being taken down the cop shop for no other reason other than being black and you just had to put to up with it. We were a precursor to all that stuff, people putting those issues on the agenda and all the riots that followed afterwards.

So let’s go back in time to the 1970s. You’re singing in pubs and clubs for not very much. You join The Selecter where you’re the lone woman- the front woman no less in a male dominated scene on tour with the likes of Madness and The Specials. What was that like? What prepared you for that? Can anything?

Nothing prepares you for being on a coach with 21 guys, believe me! But it was great and I was pretty much making it up as I went along but when we got on stage, we all knew what to do, what we were up against and what we wanted to say. The other 23 hours were a different story though!

You left The Selecter later and the band broke up soon after in 1982. You then went on to pursue a successful acting career. What were your motivations for leaving and how difficult was it to turn your hand to another career?

Well basically, I couldn’t see The Selecter going any further and then there was infighting…I just needed a break. Fortunately when I left, a film came out called ‘Dance Craze’, which was made and directed by Joe Massot and he had footage of loads of the bands on 2Tone. Around that time a film called ‘Quadrophenia’ came out and I went with Joe to the premier at the Astoria in London and met Trevor Laird, who was the black pill-popping rude boy in the film. I remember being pursued around by him and Phil Daniels and they were like “You need to be in Trevor’s play!” Then somebody told me about an audition at the Tricycle Theatre and I went for it! I was lucky to get that and be part of an establishment that was a pioneer of originating black theatre at that time.

Let’s talk a bit about your autobiography, ‘Black by Design.’ What inspired the title? I read that you changed your surname from Vickers to Black to confront ‘the elephant in the room’, as you put it: your race.

Yes. In a nutshell on one level it’s exactly that. I was working as a radiographer at the time when The Selecter was coming up and I’d be taking days off sick and I thought I needed a name change to cover my back! So the band and I were sat around thinking “Pauline…Pauline…Pauline’s black…” and I said “That’s it! Pauline Black” and it fit me like a glove. It just took me back to my family, my adopted family not using the dreaded word [black] because they hated it so much. They called black people ‘coloured.’ In a way, I’ve always been influenced by women like Freida Kahlo- she puts herself at the forefront of her art, Tracy Emin does the same. That’s what I do with my music. I talk about what I talk about because it needs to be talked about. People don’t talk about mixed-race people. We know about slavery and the southern states of America, but we don’t talk about all these mixed-race people farmed out to white families in the 50s. That story never gets heard, but there’s an awful lot of us. I thought that I wanted to be that voice for anyone who has had that experience.

Was there any trepidation or fear before writing your life story? You’re very candid in the book. You don’t sugarcoat anything. Were you worried about the reaction at all?

No, you can’t be worried about the reaction to a book. All you can do is try and approximate the truth as you see it as well as you can. I’m a pretty plain speaking person and prevarication’s not my thing. I had something to say. The book is a collection of stories about a life and I felt that some humiliation might be felt about the conditions of multicultural Britain in this time. I mean, what we are now whether we like it or not- whether David Cameron likes it or not, is a multicultural society. We’re living it and getting on with it.

How has the reaction to the book been so far?

What I like most is that people really respond to the early part of my life. I didn’t realise that what happened then- which was extremely difficult for me in terms of my parents and their friends, was seen as what it is now. For me, it’s just how I grew up.

I remember one bit of the book when you talk about your interest in the whole Black Power movement in America. You grew an afro and your mother called you a golliwog.

Yes, but she didn’t mean it like that. That was the reference point at that time but now it’s a whole different context. It carries a different kind of weight. I remember doing a book reading in front of a black audience and the interviewer brought that passage up and people were flabbergasted.

It’s fair to say you’re a pioneer in terms of music and style and also being a female front woman. You can see your imprint on bands like No Doubt and in terms of style, with Janelle Monae. How does it feel to have inspired people like that?

It’s really, really nice to know people have looked back historically and taken inspiration. I came up with not many women around, but the ones that were…I mean people like Chrissy Hynde were really brave, pioneering and revolutionary. In Polystyrene’s case- she was a black woman with her own opinions. I mean I read an interview where Gwen Stefani cited ‘Bite the Bullet’ as one of her top five albums, I felt like, ‘Yes!’

Are there any artists today that you’d like to work with?

Obviously, one that we all wanted to work with because she enjoyed 2Tone so much was Amy Winehouse. In my opinion she was one of the best talents on the planet. We did a cover of ‘Black To Black’ and recorded it, then someone told me the news that she’d died.

What’s next for you?

We’ve got a new album out on September 4th called ‘Made in Britain’ and it very much goes in to those questions of multiculturalism in this country. All of us in the band, represent multicultural Britain. This is where we’re going and we need to talk about it so we don’t have another situation like what happened in Norway.

Black By Design, by Pauline Black is on sale now (£12.99. Serpents Tail)