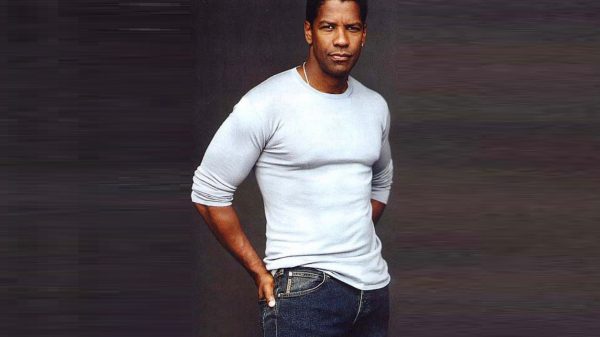

Pride caught up with the prolific actor to discuss his role in the West End production of Driving Miss Daisy, receiving an Oscar and black actors in Hollywood.

You’re currently starring in Alfred Uhry’s Driving Miss Daisy at the Wyndham. The play explores a lot of themes such as race, prejudice, as well as the relationship between Hoke and Miss Daisy and the changing face of America. What attracted you to the role?

To answer that question, which covers an immense territory of American history and American thought, I will use an immense number of words. What attracts me to Driving Miss Daisy is the way that Alfred Uhry depicts racism. First, he does not polemicize about the evils of racial bigotry. He simply tells the story of three people living their lives as best they know how at a time that falls between the failures of post-Civil-War reconstruction in the South, up to the tumultuous beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement. When Andrew Johnson took over the Presidency after Lincoln’s assassination, he essentially said to the former Confederate States: “You can no longer enslave black people! Short of slavery, you can do with them whatever you want!” Though it came in the later decades of that time, Driving Miss Daisy occurs in the worst state of segregation— when it was atrophied and seemingly unmovable. Where white people had great privilege, black people had great deprivation. That was a world I was born into in 1931 Mississippi. That was the world of Alfred Uhry’s characters. They were not invented— these were people he knew quite intimately. Daisy was his grandmother. Hoke was her driver and as much as that society allowed, very much a part of the family. Boolie, Daisy’s son, is a composite character whose generation lay between the two. Alfred Uhry did not create an illiterate black man for the hell of it. The dialogue that I delight in reciting on stage is the way Hoke talked. He took the few words and phrases he picked up in his life and created a very effective and poetic form of English that served him. Some black people may be embarrassed by his language, but I have Southern members of my family who are just as illiterate and just as poetic, and I am very proud of them. In spite of being deprived of education, Hoke is dedicated to educational upward mobility for his family—his children and grandchildren—and his work ethic is guided by his need to contribute whatever he could earn toward their tuitions as long as he was able to work. Employment for people like Hoke had to come from white people—some openly racist; some, like Daisy, only unconsciously so—but they were still the only source of employment. Hoke himself is not without his own biases. He has disdain for fellow black people who don’t strive for better education, and he has loathing for hypocritical white people. He learns from Boolie, Daisy’s son, how to deal with her, and in a way, to understand her acerbic and fierce sense of independence. Probably a sweet or kind word has not passed her lips since her husband died. Boolie bears the brunt of most of her fierceness, but when Boolie hires Hoke to be her driver, Miss Daisy responds to losing her driving privileges by turning her fierceness on Hoke. He works with that fierceness with patience, partly because he admires her independence, and partly because he really likes her son and the job he’s given. He likes his job because he knows he’s good at it so he takes it from Miss Daisy, and occasionally gives it back. Racism is never discussed in the play—barely even mentioned, except twice by Miss Daisy when she defensively says, “I’m not prejudiced” (and she truly believes she is not, but learns more and more reluctantly how much the segregation system has affected her). Throughout the play, racism leeches up through the people’s lives and their relationships like the virus that it is, and as far as I’m concerned, there’s no better way to tell the tale of a social problem except through the people who suffer through it.

What motivates you in picking your roles? Do you feel a responsibility to portray certain roles?

I choose roles by my judgment as to my ability to carry it off. Can I be clear with what the character says? Can I be revealing? Is it worth telling? My only responsibility is to the writer; the character is his vision of a human being, after all.

Two years ago, you were here in London doing Cat On a Hot Tin Roof. How was that experience? How does West End theatre compare to Broadway?

Big Daddy and Hoke are at opposite poles of humanity. Big Daddy (Cat On a Hot Tin Roof) is cruel and ambitious in contrast to Hoke (Driving Miss Daisy), who is patient and simple. Big Daddy has a possessive affection only for his son. Hoke loves all his children and grandchildren and knows they, with his help, will have a better life. All these men have in common is they are Southern men. Big Daddy’s language is crude, coarse, and vulgar; Hoke’s language is inarticulate and illiterate, though as I’ve said, quite creative and poetic. He uses English as best he can, discarding rules of grammar that don’t serve him. Our producer for Cat On a Hot Tin Roof, Stephen Byrd, scoured the churches and comedy clubs of London, and the military bases around London, and brought in a new black audience that I did not know existed in London. He also got the Tennessee Williams fans and students to come out in droves. He had achieved the same thing in New York.

You’ve done it all. You have critical and commercial acclaim. It would be very easy to bow out and just take all the plaudits. What motivates you to continue?

I am motivated to continue as an actor because I genuinely love the work. I don’t feel I’ve “done it all”. In spite of some movies that I’m very proud of, I don’t think I’ve yet done that film I can leave as my legacy. I am yet a journeyman actor who works for a living.

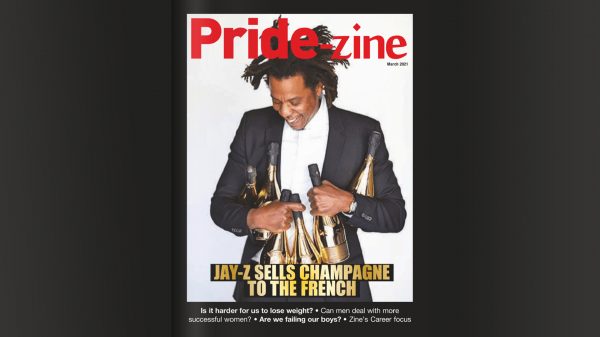

This year it was announced you’d receive an honorary Academy Award. How much does that honour mean? At this stage in your career how much do awards still mean to you?

The honorary Academy Award means a great deal to me. I honor it as it presumably honors me. My wife and I couldn’t stop laughing with joy about it. Just think: I got an “Oscar” without having to compete, or campaign, or advertise, or fight for it. Perhaps it’s testimony to having hung in there or simply having been around too long to ignore, but make no mistake—this golden statue goes on my mantle.

Quite remarkably for a black actor in Hollywood you’ve managed to portray a variety ofcharacters. You’ve done serious drama, comedy, TV, film, action. You seem to have managed to escape typecasting in a way a lot of other black actors haven’t. Why do you think that is?

The variety of acting forms I’ve worked in can be explained by the way I began as an actor. In the late 1950’s, I saw there were not enough work opportunities in any one field so I decided to try to “walk on as many legs as I could.” Stage, film, radio, commercials, TV—well, they alone make me a quintiped and I can’t say which I like best except that I got my initial training for stage.

How do you think black actors are faring in Hollywood today? Do you think there’s still a glass ceiling in terms of quality of roles and variety?

I don’t have a clue. It’s not that I don’t care, but acting in the movie industry is an unusual form of employment. It requires an intricate confluence of elements: the right casting, the right writing, the right directing, all have to converge at the same time. There’ve been a couple of movie stories I have liked over the past couple of years, but the timing was never right. As far as ethnic performers are concerned, the opportunities are not only based on fate. When writers do more stories about ethnic life, or directors ignore ethnic lines and cast more freely, the field of work can broaden.

The film industry is quite cyclical. The remake of Conan the Barbarian came out recently and you starred as Thulsa Doom in the original back in 1982 with Arnold Schwarzenegger. Have you seen the remake? Were you for or against it?

Sometimes, sequels and remakes can indicate a poverty of imagination among writers, but I will never miss a remake of The Thing, and I understand there’s one coming. Regarding Conan—first of all, there was no particular reason I should have played Thulsa Doom. It was John Milius’s idea. He had written a lot of speeches derived from the sayings of evil men throughout history, so he put a Teutonic wig on my head, placed me at the top of a canyon in southern Spain overlooking the Mediterranean, and told me to cut loose. No, I have not seen the remake; if it is good, I will cheer. If it is not good, I’ll be respectful, because obviously a lot of people put a lot of hard work into it anyway.

It’s a tough question but which roles are you most proud of? What are the favourite films you’ve done?

No, that is not a tough question. My favourite roles are version of what Shakespeare called “The Elemental Man.” Men who have nothing to lose, nothing to gain, nothing to hide, or sophistication or manners or pretentions with which to hide anything. Lenny Small in Of Mice and Men is such an elemental creature. Hoke is one. And, except for his religiosity, Reverend Stephen Kumalo in Cry, the Beloved Country is one, and he is partly the answer to the question of my favourite movie—that is, Cry, the Beloved Country.

Who are the best actors or director’s you’ve worked with in your storied career?

Judging the “best” requires deep and sometimes painful comparisons. I don’t think any of us are comparable.

About ‘the voice’. To this day can you comprehend the attention that’s been given to something that’s so normal to you? Mufasa, Darth Vader… how does it feel to be recognisable not only visually, by name, but also vocally?

The voice is in the ear of the listener. I was trained not to listen to my voice, so I don’t know what to say about it.

Driving Miss Daisy is on at the Wyndham theatre until December 17th 2011