The UK’s top soul songstress tells Nicole Vassell about colourism, gratitude and the importance of believing in your own talents as she celebrates her 25-year career

Beverley Knight is focused. With her head down and her pen deftly writing her name again and again, she’s signing 500 copies of her latest album, BK25, for fans, and when I enter the room for our interview, she’s on her last 50 sheets. With members of her management team also in the room, discussing her plans for later in the day, and busying themselves with other various tasks, you may think that this would be a distraction from the tedious task at hand. However, Knight manages to greet me warmly, respond to their questions and make her lunch order, all while concentrating on the task in front of her.

This sense of being able to do many things at once while keeping her eyes on the prize is, perhaps, symbolic of her career thus far. Celebrating 25 years in the music industry this year, Beverley Knight is undoubtedly an essential part of the British entertainment landscape, and even more so a significant figure amongst Black Britons. Her accolades include Mobo Awards, Brit Award nominations and an MBE for her contributions to British music, as well as highly rated turns as an actress in London’s West End.

It’s no easy feat to reach a milestone like this, and it’s not one that Knight takes for granted. Listening to the live album, which is accompanied by the Leo Green Orchestra, there’s barely a song that passes without Knight saying ‘thank you’ to the enthusiastic crowd at London’s Royal Festival Hall. There’s an atmosphere of electricity and mutual appreciation, and it’s a really fitting way to mark her years of impact. When I mention this feeling of gratitude that flows through the record, she has a simple justification: her fans continue to show up for her.

‘People don’t have to be there,’ she explains. ‘They could choose to be anywhere in the world at that given time, but they chose to spend their money on tickets to see me do what I do, and have done for a long time. They could be fans of anyone but they’ve chosen to be there with me – and that’s a big deal. So you let people know that that means something to you.’

Born and raised in Wolverhampton to Jamaican parents, Knight has had music in her life for longer than she can remember. From singing in church to writing her first songs as a young teen, music runs through her and has come out in the form of eight solo studio albums, leading roles on London’s West End stages and countless live performances that leave each audience thrilled by her impressive vocal ability. She’s someone who, upon hearing her, you believe was born to sing, and in an ideal world, she’d be known worldwide with the name checks to match.

However, getting her foot in the door was far from a cakewalk; despite her incredible talents, debuting as a Black female artist in early 1990s Britain meant a challenge to be taken seriously.

‘It’s never been a straightforward path; I’ve had to fight for absolutely everything,’ she tells me. ‘I’m British, I’m a woman, I’m Black – and I’m not just Black, I’m dark. I’m all of those things in a country which typically didn’t want to know. I started off in the middle of the Brit Pop era – white, male, shoegazer guitar bands – and then there’s me, the absolute opposite to all of that, starting off my career. So it’s never been an easy road.’

With the knowledge that carving a way for herself was going to take some work, Knight armed herself with education to show any doubters that she was not to be underestimated.

‘I was offered my deal when I was 19, and about to do my degree. And remember, this was the early nineties – it was pre-Blair, for a start, and Britain was a different place. But I didn’t abandon my studies because I wanted them to know that I was a thinking Black woman. You weren’t gonna be able to word salad me or put ideas into my head of what I am and what I’m about easily.’

How fortunate that this steadfastness in knowing who she is was there from the very start; without it, who’s to say that she wouldn’t have ended up forced into musical shoes that didn’t quite fit and quickly cast to the side – the fate that others, though deserving of attention, have faced. For young Black women especially, Knight’s actions are nothing short of inspiring; standing her ground, and setting out the standard of the kind of artist she wanted to be from the start has been essential to her longevity, which has in turn built the foundations for Black British artists who’ve started their careers in the years since.

On working to catch her break in the British music industry: ‘I knew I was damn good at what I did, and that could not be denied’

Looking at the music of today, Knight’s charmed to see much more of a share of Black artists getting their due, compared to the climate in which she started off: ‘You could count on one hand the Black British artists that had much meaning to a wider British public – which is really heartbreaking. Now you have people like Stormzy, who’s conquering the whole world, which is wonderful.’

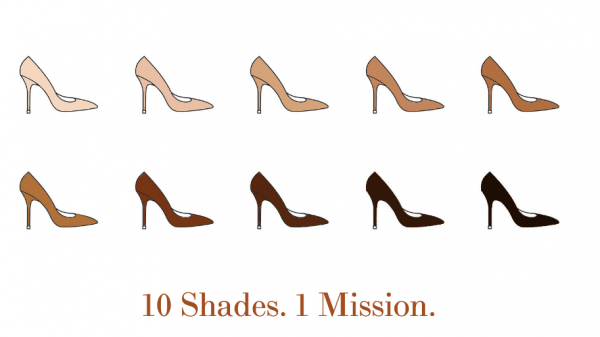

However, nothing’s perfect: for Knight, it’s worth mentioning a disparity between genders – and an issue of industry preference of Black and mixed women who have lighter skin tones.

‘When I look at the women in music, I feel as though things are creeping forward, but it’s not the leap that the guys have made,’ she says. ‘And there is still a colourism issue around women – which is ancient, and even today we’re still not quite past that. When I look around, I’m the only one of my hue who is known in the mainstream. Everyone else is way lighter. In so many ways, we have leapt forward, but it hasn’t been the same for women.’

It’s refreshing to hear Knight touch upon this topic of colourism so freely; though you’re much more likely to hear celebrities discuss it in recent years, for some, it can still be an awkward experience to address. Knight credits social media as one of the things that have helped expand this conversation further.

‘We knew it existed – we knew,’ she chuckles, conspiratorially, ‘but social media, thank God, has allowed for colourism to be talked about, debated, exposed. Before, you didn’t have a mass way of communicating these kinds of feelings; you didn’t know that people beyond your own little [group of] friends were thinking the same. You suspected they did, but if you didn’t read it in Pride, or in Essence magazine, as far as you were concerned it wasn’t a topic. But it’s always been there. Social media has opened all of that out, so we are talking about it and we are encouraging ourselves to see ourselves differently and then hopefully outside of our race people will get with it as well.’

In terms of speaking openly about difficult topics, Knight is also candid about the respect that radio stations lacked when it came to music by Black British artists when she started: ‘In some areas, it was outright hostility – or it’d be patronising, or they would just blanket ignore. If you weren’t coming from the States, you were always treated as the second class, inferior.’

Being a time before the internet offered alternative means of sharing your music with the world, the backing of the radio and the media was a key source for an artist’s success. It’s not hard to imagine how frustrating it must have been to be ignored – and to know that the reason behind is rooted in biased judgements. I ask her how she stayed determined to break through, despite this sense of apathy from those with the power to publicise her – and to my delight, she answers matter of factly in a way that’s instantly inspiring, and unfortunately, feels quite radical: an unwavering sense of self-belief.

‘I knew I was damn good at what I did, and that could not be denied,’ she states baldly. ‘No snippy, cynical comment by a women’s magazine, or a thinly veiled dig or whatever from a tabloid, none of those things could make me question whether I was any good. I knew I was, and I knew I was, unapologetically. And I also believe strongly that the world comes round to where you are; you don’t have to chase them. It might take some time, and it might take getting a lot of stick for it. But eventually, people understand where you’re coming from.’

As well as her established role in the hearts of the fans, since 2013 she’s also taken on the role of West End star, with leading roles in The Bodyguard, Memphis and Cats introducing her to a new fanbase – to the extent where some are surprised to learn of Beverley Knight, the theatre actress, having a long history as a recording artist. In 2017, she brought her two worlds together for an album with fellow musical theatre actresses Amber Riley and Cassidy Janson; titled Leading Ladies: Songs From The Stage, the album was a success, reaching the UK Top 20.

Soon, there’ll be a new West End show in the works; although she keeps her lips sealed about what exactly the show is, she ensures me that it’ll be out in 2020 and will be ‘really fantastic’. And as for future milestones, Beverley Knight already has her sights set; the hustle isn’t about to stop at year 25 when there’s so much more she’s aiming to achieve.

‘In 25 years, the shelf will have Grammys, it’ll have Tonys, for sure – and there damn well should be some Oliviers up in there!’ she proclaims. ‘In 25 years, maybe there’ll be a Lifetime Mobo Award to add to the others, that’d be good. And I’d be doing BK50 – that’s absolutely the plan. Listen, Tony Bennett is in his early nineties and he’s still singing really well. Cicely Tyson is 94 – look at her! Look at the woman. That’s what I’m aiming for.’

Seeing how far she’s come, it’d be foolish to doubt that she’ll make it happen.

BK25: Beverley Knight with The Leo Green Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall is out now