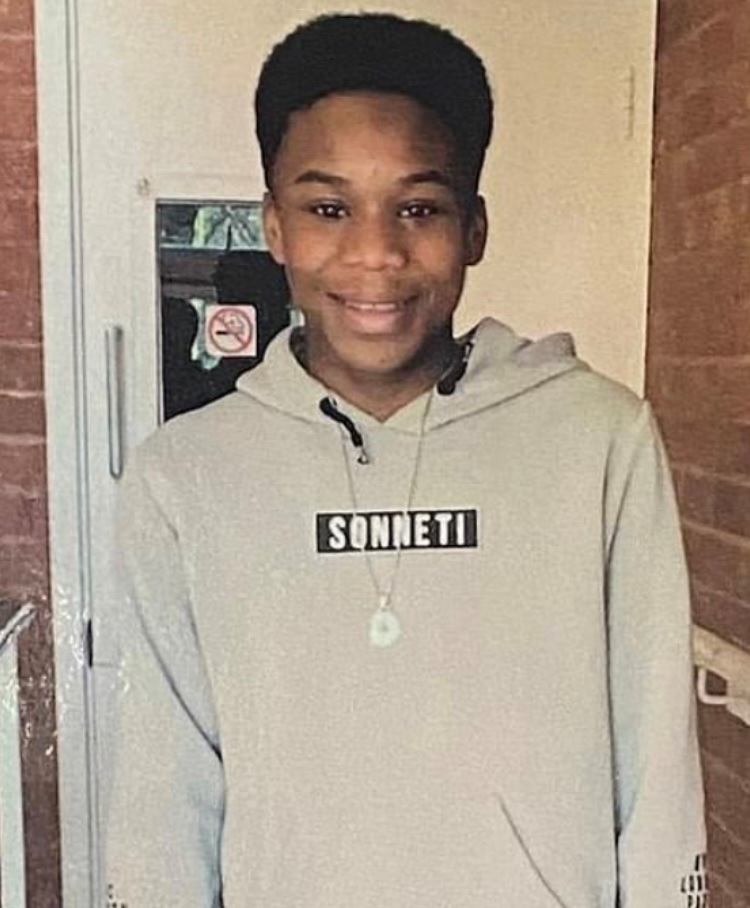

When Seymour Reid went to lay a wreath on his 14-year-old son’s grave last week, he thought his legs would give way. “My child is dead and gone,” said the father. “Nothing can bring him back. We cannot dig him up, cannot put breath in him.”

At 7.30pm on May 31 last year, while it was still light, Dea-John Reid was chased down a busy street in Kingstanding, Birmingham, by a group of five males, most of them white, who were shouting racist slurs. One of them, 14 at the time, killed Dea-John with a single blow to the chest with a knife. Now 15, he was acquitted of murder by a jury but found guilty of manslaughter. He cannot be named because of his age. The other four people in the group were found not guilty of joint enterprise.

His family believe that “justice has not been done” and that the largely white jury was not representative of the Birmingham community. They plan to launch the Justice for Dea-John Reid Campaign to fight for juries to be ethnically diverse.

“Dea-John was a 14-year-old black boy who was chased by a lynch mob and knifed to death,” the Right Rev Desmond Jaddoo, the family representative, said. “It is open season on the black community and we can’t allow that to happen. We need ethnically balanced juries in race cases. Everyone taking the knee two years ago, what was that? A fashion statement?

“Dea-John’s civil rights [were] completely abused. This system is not geared up to give black people justice.”

In England, there can be no challenge to jury selection, for example if it is all male or lacking in racial diversity. No principle dictates that a jury should be racially balanced. A jury must be impartial and independent and the prosecution can challenge an individual juror on the basis of being ineligible “for cause”, such as a connection to the trial.

Recent cases in the US, involving all-white, or overwhelmingly white, juries, including the murder trial of three white men over the death of Ahmaud Arbery, a black jogger, in 2020, have provoked debate about racial bias. In America, both the defendants and the prosecution can challenge the jury selection and jurors can be struck off, although not on account of their race.

Richard Wormald QC, the prosecuting barrister, said the attackers behaved “like a pack” and “hunted down” Dea-John. Witnesses heard them say: “Get the black bastard.”

As well as the 15-year-old convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to six and a half years in detention, the attacking group was made up of George Khan, 38, Michael Shields, 35, a 16-year-old and a 15-year-old. It was called a “revenge” attack for an earlier provocation. The family see the single-person sentencing as being too weak. “I have had to sit through a trial where I am told that justice will prevail,” his mother, Joan Morris, wrote in her victim impact statement. “I do sincerely believe that the system has let me down.”

She said: “This verdict of manslaughter, whilst the others are all found not guilty, just goes to prove to me that the life of my son, a young black man, did not matter.”

Tim Clark QC, for the defence, said: “[The defendant] accepts he caused the death of Dea-John but did not intend to kill him. He was acting in self-defence.”

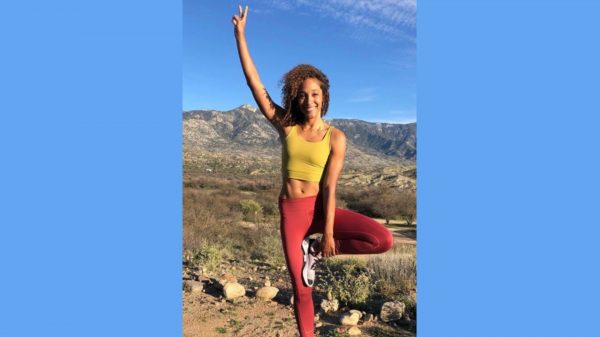

Dea-John’s parents described their son as a ball of energy, doing endless backflips across the park and obsessing over keepy-uppies.

He lived with his mother and Kirk Bryan, his brother, in Edgbaston, a mile south of Birmingham city centre. He was a bright pupil at Harborne Academy and wanted to be a dentist.

“I still walk through this city and I look out for him around the next corner,” his father said. “I ask, please God, work a miracle so I can see him again.”

It was a balmy May bank holiday Monday and Dea-John was in Kingstanding with friends. There was an altercation between groups and one group of teenagers went into a nearby home and one grabbed a kitchen knife. The others said they did not know he had the weapon.

The killer phoned Khan, 38, who was drinking with Shields, 35, in the Digby pub in Erdington. They collected the three boys in Khan’s car and “set off to hunt down the Dea-John group”, Wormald said. “[The teenagers] sought help in the form of the two older male defendants. Khan carried the plan to seek retribution forwards and actively encouraged the attack.”

Dea-John’s group were in the park when, according to a witness, Khan pointed and shouted, “Oi, you n*****s”. Dea-John darted in a different direction from the group to get away. Khan parked his car and the defendants ran after Dea-John. “They had agreed to act together,” Wormald said. “This was a concerted plan … like a pack in chase.”

At the sentencing Clark said: “But for George Khan putting a posse together, this would not have happened. But for George Khan inciting [the boy] to at the very least chase after [Dea-John Reid], it is unlikely that this violence would have ever occurred.”

According to CCTV pictures, Dea-John, who had asthma, ran out of breath, turned to face his attacker and put out his arm when a single, fatal blow was inflicted to his heart. He died quickly. A vigil held in the days after Dea-John’s death was attended by hundreds of people and raised tensions in the local community as reports circulated that he had been racially abused before he was killed.

A family friend, Michelle Helsby, said: “I don’t understand how they walked away from it … It was a racially aggravated murder. Black lives don’t matter.”

In the eulogy at her son’s funeral Morris said: “Every morning I wake up and I still look forward to you coming into my bedroom and asking how I was. Every time my phone rings I hope it is you. Dea-John, I miss asking you to make a cup of tea for me.”

She broke down in tears after the sentencing, repeating: “My boy, my boy.”