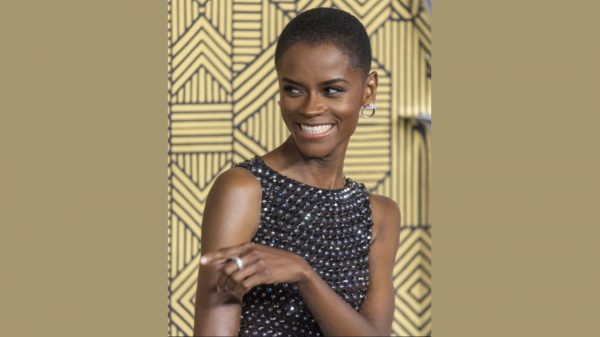

“You might carry the gene (or trait) for sickle cell disorder and not even know it, ”says Virginia Tshibangu, a Clinical Nurse Specialist for Adult Haemoglobinopathies at Kings College Hospital, London.

Particularly affecting those with an African or African-Caribbean family background, around 17,500 adults and children have sickle cell disorder (SCD) in the UK. It is also one of nine rare but serious conditions babies are tested for at birth through the neonatal screening programme.

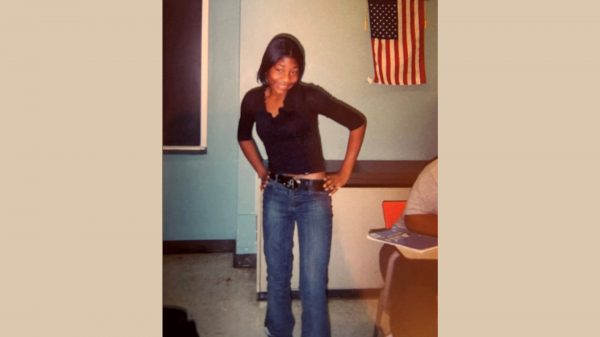

“As myself, siblings and close family don’t have sickle cell disorder (SCD), I didn’t know that I was a carrier until I was pregnant,” Explains Virgina. “If both parents have the condition or carry the gene, their child could inherit the gene from each parent and have this serious life-long condition.”

What is sickle cell disorder?

“Red blood cells are donut shaped,” says Dr Kilali Ominu-Evbota, co-lead of the Mid and South Essex Paediatric Sickle Cell Service. “For those with sickle cell disorder, it affects the hemoglobin in the red blood cells causing the cells take up a sickle or – what I like to call – a banana shape.” It can also lead to haemolytic anaemia – a blood condition that occurs when your red blood cells are destroyed faster than they are replaced.

Stephanie George, 33 says the disorder is unpredictable. “There have been days where I’ve woken up feeling fine, yet later that day I am in A&E having a Sickle crisis.”

Dr Ominu-Evbota explains a crisis occurs when the banana shape of the red blood cells, causes them to get stuck within blood vessels which can restrict the flow of blood and oxygen around the body. “As well assevere pain, without treatment this can lead to other complications including stroke and organ failure that can be fatal.”

| o Pain

o Signs of infection including fever o One-sided paralysis or weakness in the face, arms or legs o Confusion o Difficulty walking or talking |

o Sudden visual changes

o Unexplained numbness o Severe headache o Breathlessness, chest pain of low oxygen levels |

|

These symptoms might indicate a sickle cell crisis or other complication. |

Living with SCD

SCD can be debilitating in many ways, says Stephanie. “I had a stroke as a child, as a complication of having SCD. I must make sure that I don’t get too cold as that could trigger a crisis. I must take my medicines everywhere with me and know where the nearest hospital is, just in case I have a crisis. I’ve also needed regular blood transfusions since I was a child.”

“You don’t grow out of it,” says Virgina “you try and manage it with medications that seek to reduce the frequency of crisis, and pain relief once in crisis.”

Dr Ominu-Evbota explains a blood transfusion might be given in an emergency, “To improve blood flow and prevent a stroke and other complications”. Or can be used as part of a regular treatment plan, “to reduce the risk of blockages or to improve how much oxygen can be carried, by replacing their banana shaped red blood cell with healthy blood cells.”

Virginia adds “Viruses and infections can reduce your hemoglobin, resulting in anaemia which can leave you very ill. So, we have to watch out for any illnesses and will speak to our patients and their families about the importance of vaccinations.”

Can it be cured?

“Hope is on the Horizon,” says Dr Ominu-Evbota.

Children and adults over the age of 12, with a severe form of sickle cell disease marked by lots of recurrent sickle cell crises, who would be suitable for a stem cell transplant but where a donor is not available might benefit from a groundbreaking new gene therapy. Known as exagamglogeneautotemcel (or ‘exa-cel’), clinical trials suggest this therapy can stop painful and unpredictable sickle cell crises. Furthermore, all patients who received exa-cel also avoided a hospitalisation for a year following treatment – and almost 98% had still avoided hospitalisation around 3.5 years later.

The cutting-edge treatment each year could be offered to people for whom the benefits outweigh the potential side effects that could come with the treatment and the upheaval needed in preparing for it. They will need to attend a specialist NHS centre (based in London, Manchester and Birmingham).

Faster care in a sickle cell crisis

For those adults and children who are not eligible for therapy, the NHS is continuing to work on ensuring that people get the care they need and faster.

“Everyone should have a care plan,” says Virgina, “this lets everyone know what medications you take at home if you have a crisis and what medications you should have in hospital to help control your pain.”

Care plans are co-developed by patients with their specialists – which is important to ensure they support people in their day-to-day lives as well as when they have a crisis or need hospital care. The NHS in Manchester and London have digitised their care plans, with other area’s being supported to follow. This makes it easier for every clinician who needs to access your care plan, to do so, and allows them to update your care plan too, to better join up your care between different healthcare professionals. “In London, the Universal Care plan can be seen by hospital staff, GP practice and community staff and even the paramedics called to assist you,” explains Virginia.

The NHS is also rolling our seven new Sickle Cell Emergency Department By-pass units across the country. Four of these are already up and running in London, Manchester and Sheffield. These specialist units support patients in sickle cell crises to get the care they need as soon as possible by bypassing EDs and going straight to healthcare professionals with specialist sickle cell training to get pain relief and other treatment faster.

“Getting effective pain relief, care and treatment is so important,” says Stephanie. “The pain is excruciating. You don’t know when it is going to end, and it can get worse and worse. There have been times in my life, when I have really thought I was going to die, because the pain has got worse and worse and it’s a scary feeling.” Stephanie adds, “It is so important that all health professionals can identify a sickle cell crisis and understands how and why to treat it fast, as the medical emergency that it is.”

To help ensure that every hospital can deliver rapid and effective care to patients, NHS England launched a national campaign, Can you tell it’s sickle cell to support doctors, nurses and other staff to spot the signs of a sickle cell crisis. In addition to this, Virginia has been supporting a new approach called ACT NOW.

“Our ‘ACT NOW’ guidance, has been co-designed with people with sickle cell disorder, their families and health professionals like me,” says Virginia. “The guidance is available to clinicians across the country and encourages rapid and effective care for patients in sickle cell crises. It also reminds clinicians to think about the other things that really matter to you, such as making sure that we keep you warm, as being cold can trigger or worsen your crisis.”

Donating blood can save the lives of people with sickle cell

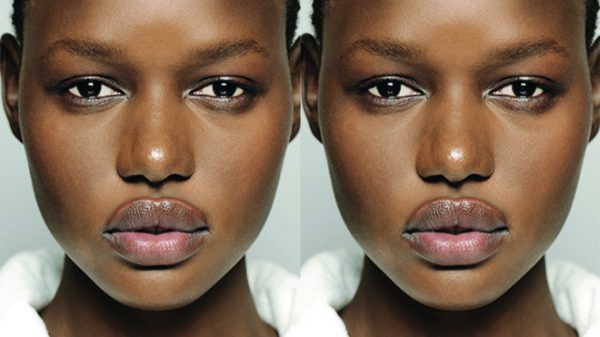

The majority of people with SCD in England come from a Black background and many will need a blood transfusion at some point in their lives and around 20% need regular blood transfusions, sometimes needing up to 90 units of blood a year.

Dr Sara Trompeter, a Consultant Haematologist at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and NHS Blood and Transplant, explains how people SCD will often need blood from people with a Black background.

“Whilst you might have heard of blood groups A, B, O and D, there are actually, more than 300 different blood groups,” says Dr Trompeter. “People from a Black background often have a very different set of blood groups than those from other ethnic groups which is one of the reasons why we need people from a Black background to be blood donors.

“The closer donated blood more closely matches yours, the less likely it is that you will have a reaction to the blood such as form an antibody. Forming antibodies to blood can result in severe life-threatening reactions and make it very difficult to source blood in the future.”

NHS Blood and Transplant is looking for ways to make blood transfusions even better matched for people with blood disorders. The first step is to make sure we understand the extended blood group of our patients and our donors, and that the testing that is used is adept at picking up the rarer blood groups seen in people from a Black background.

NHSBT has introduced a new test, funded by NHSE and developed by the Blood transfusion Genomics Consortium, which is being offered to people with sickle cell, thalassaemia and people with rare inherited anaemias. This test uses genotyping technology, a way of testing blood groups using DNA, which is a better technique to pick up some of the rarer blood groups seen in people of from Black background. It is also a faster test and can be done at scale, so the hope is that NHSBT may be able to use this test for donor testing too, to increase the numbers of donors with extended blood group testing.. We would ask all patients with these health disorders to discuss sending a sample with their hospital teams when they are in for a transfusion, check up or otherwise.

To find out more and become a blood donor via the Give Blood NHS app or at www.blood.co.uk. For more information about blood group genotyping visit NHS Blood and Transplant.

“We have blood donation sessions around the country, including a new donor centre in Brixton and donor centres in Stratford, Tooting, Colindale and the West End,” says Dr Trompeter. “Please give blood, you will save and improve lives.

“And if you have sickle cell, thalassaemia or receive transfusions for your rare inherited anaemia, please ask your hospital team about the genotyping test – you could receive better matched blood.”