A fews ago the lack of racial diversity in Ballet was one of the dance world’s most-discussed issues. Among the top international companies, few rosters included dancers of non-European descent. In the United States attention focused on the absence of African Americans and other women of colour from many of the country’s premier ballet companies.

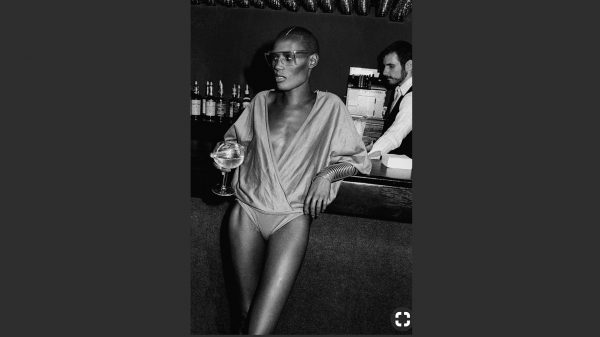

Misty Copeland in Swan Lake On June 24, 2015, American Ballet Theatre ballerina Misty Copeland (partnered by James Whiteside) spellbound audiences at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City with her performance in Swan Lake in the double role of Odette/Odile; she was the first African American to star in Swan Lake for ABT, and a few days later she was promoted to principal dancer.Julieta Cervantes—The New York Times/Redux.

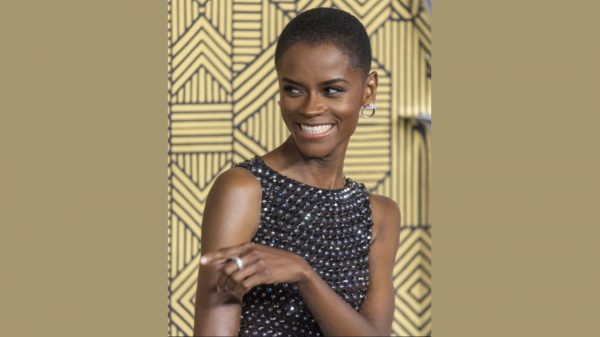

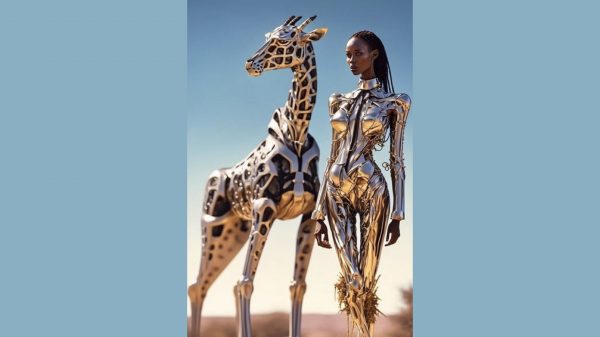

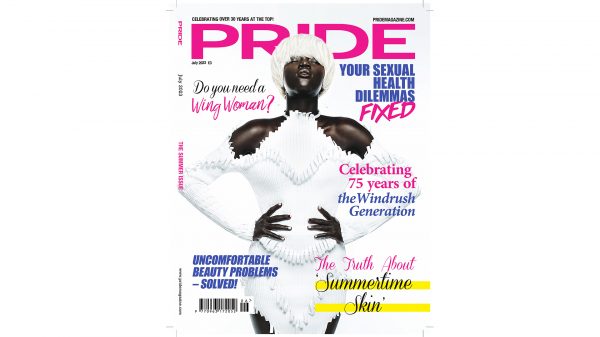

Ballerina Michaela DePrince performs with the South African Mzansi BalletMichaela DePrince performs as a guest artist with the South African Mzansi Ballet at the Joburg Theatre, Johannesburg, where she shows off her magnificent form in the final rehearsal prior to her debut as Kitri in Don Quixote.EPA/Alamy

In April a special staging of Swan Lake at Washington, D.C.’s Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts highlighted that disparity. For two nights only the Washington Ballet (TWB) brought together American Ballet Theatre (ABT) soloist Misty Copeland and TWB veteran Brooklyn Mack to dance the leads in ABT ballet master Kirk Peterson’s reconstruction of Swan Lake, featuring the choreography of Marius Petipa and his assistant Lev Ivanov. Copeland and Mack, as Odette/Odile and Prince Siegfried, respectively, were remarkable for their dancing. However, their performance also won acclaim for another reason. TWB’s artistic director, Septime Webre, defied expectations by casting Copeland and Mack, both African Americans, in the most revered of the “white ballets.” Although the moniker ballet blanc denotes the hue of the tutus worn in Swan Lake, Giselle, and La Bayadère, the term might just as well describe the apparent racial makeup of many ensembles that perform those works. Dancers of colour rarely are given the opportunity to appear in that repertoire, because they are often typecast in pieces that require extreme athleticism as opposed to classical lines. The exquisite dancing by Copeland and Mack, however, challenged such racial stereotypes.

Ballet, which had origins in European court dance, in the 21st century remains an entertainment for the well-to-do. High ticket prices often limit the art form’s accessibility to economically disadvantaged audiences, many of whom identify as racial minorities. That same inequity can discourage children of diverse backgrounds from studying ballet. In addition, many companies and schools endorse retrograde aesthetic values that place dancers of colour at a disadvantage in the realms of hiring, casting, and promotions. Classical choreography often relies on the female members of the corps de ballet, a large group of women who not only move as a single body but also share a common body type. The preference for a homogeneous corps de ballet privileges Eurocentric ideals of beauty before racial diversity. For all of those reasons, there have been too few opportunities for dancers of colour.

As early as 1933 Georgian émigré and noted choreographer George Balanchine, together with his New York-born dance patron Lincoln Kirstein, set out to found a racially integrated, distinctly American school. Shortly thereafter, the men established the School of American Ballet (SAB) and a progenitor of New York City Ballet (NYCB). Although their vision of equality was never fully realized, Balanchine offered Native American and African Americandancers contracts at a time when such opportunities were scarce for nonwhites. Beginning in the 1940s Maria Tallchief, a dancer of Osage Indian and Scotch-Irish descent, performed star roles with NYCB. Tallchief was the first Native American to become a world-renowned prima ballerina. In 1957 Balanchine created Agon, a black-and-white ballet set to an original score by Igor Stravinsky. The work’s pas de deux is a study in contrasts, both of skin and of musical tones. For the iconic duet, Balanchine chose Diana Adams and Arthur Mitchell—a white woman and a black man. A video of the ballet inspired Amar Ramasar, who is of Indo-Trinidadian and Puerto Rican descent, to study dance at SAB, and he went on to become an NYCB principal. For NYCB’s 2015 spring season, Ramasar partnered fellow principal Maria Kowroski, who is white, in Agon. The pairing demonstrated the enduring relevance of the ballet as a meditation on race.

Some contemporary filmmakers are excavating the histories of African Americans in ballet, while others are telling the stories of a new generation of dancers. In February American producer and director Frances McElroy screened an excerpt from her work-in-progress Black Ballerina at New York City’s Lincoln Center. The documentary profiles six African American female dancers. In the film Joan Myers Brown (founder of the Philadelphia Dance Company) and Delores Browne (former principal with the New York Negro Ballet) recount the discrimination that they faced as women of colour who sought careers in ballet during the 1950s and ’60s. Raven Wilkinson discusses her experiences as the first African American woman to land a full-time contract with a major company, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo(BRMC). Prejudice she faced while touring with BRMC and a subsequent lack of opportunities in the U.S. led Wilkinson to accept a soloist post in 1966 at the Dutch National Ballet (DNB).

Wilkinson’s story has some affinities to that of 20-year-old Sierra Leonean American dancer Michaela DePrince. DePrince was one of six 2010 Youth America Grand Prix (YAGP) competitors to appear in American filmmaker Bess Kargman’s 2011 documentary First Position. YAGP awarded DePrince a scholarship to study at the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School at ABT, after which she joined the Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH) for one season. Like Wilkinson before her, DePrince later signed on with DNB, where she presides as the troupe’s only dancer of African origin. In 2015 Brooklyn-based filmmaker and journalist Nelson George premiered A Ballerina’s Tale. The movie follows Copeland’s career as a dancer and a spokesperson on the issues of race and body image in ballet. In 2007 she became ABT’s first African American female soloist in 20 years.

Several companies have made inroads into the problem of racial inequality in ballet. In 1969 former NYCB principal Mitchell and former DNB ballet master Karel Shook cofounded DTH, an organization committed to multiculturalism. In 2009 DTH celebrated its 40th anniversary. The following year Virginia Johnson, a ballerina of colour and a 28-year DTH veteran, assumed the company’s artistic leadership. In 2015 the troupe boasted an international roster of 18 racially diverse dancers. As part of TWB’s 40th season, in 2015 it launched Let’s Dance Together, an initiative that strives to develop future generations of racially diverse dancers and choreographers. In 2001 Trinidadian British director-choreographer Cassa Pancho established Ballet Black, a company dedicated to offering more opportunities to dancers of African and Asian descent. Two more artistic directors who advocate greater racial diversity in the discipline are Dorothy Gunther Pugh of Ballet Memphis (Tenn.) and Stanton Welch of Houston Ballet.

Within the last decade many international companies have recruited Latin American and Spanish dancers, particularly men. Those artists have begun to change the complexion of ballet in Europe and the U.S. In addition to ABT, NYCB, and TWB, troupes with large numbers of foreign-born Hispanic dancers include Boston Ballet, Joffrey Ballet (Chicago), San Francisco Ballet, and the Royal Ballet (London).

One collaborative campaign has been especially newsworthy. ABT’s Project Plié, launched in 2013, aims to encourage minorities to study dance. The outreach program forged a partnership between the Boys & Girls Clubs of America and 14 of the country’s top ballet troupes. Two social media projects use images to promote the achievements of dancers of colour. The Tumblr page Black Ballerinas and Instagram posts by Brown Girls Do Ballet feature photographs of racially diverse dancers. American TaKiyah Wallace started Brown Girls Do Ballet with the intention of photographing underrepresented female ballet students in Texas between the ages of 3 and 18. The project galvanized so much interest that it became a movement.

Balanchine reportedly called Tallchief’s 1949 debut as the Firebird in his eponymous work NYCB’s “first great success.” Roughly 60 years after that, Copeland starred in Russian choreographer Alexei Ratmansky’s new version of the ballet for ABT. Though her role in 2012 as the spitfire set Copeland’s career ablaze, classical leads proved somewhat elusive. She was, however, on June 24, 2015, the star (Odette/Odile) of ABT’s Swan Lake at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. The performance marked Copeland’s New York City debut in the role. Delicate as Odette and bewitching as Odile, Copeland demonstrated the artistic range of a principal dancer, a rank that she finally attained six days later, to become the first black Principal Dancer.