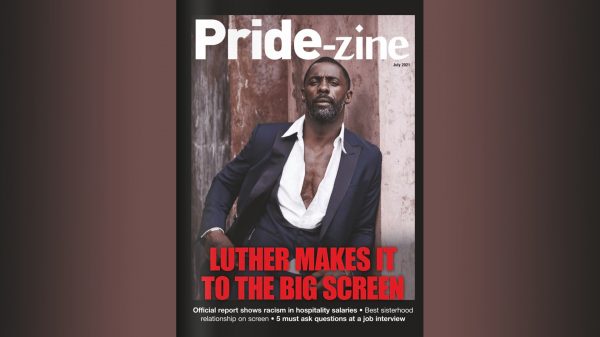

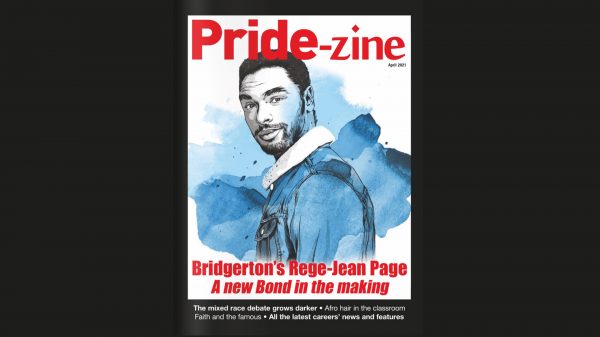

Pride magazine has been writing and campaigning for black actors to be seen in period drama in roles other than slaves and servants for many years. We are finally being heard.

We were two separate societies divided by color until a king fell in love with one of us,” the quick-witted Lady Danbury (Adjoa Andoh) tells her protégé, the Duke of Hastings. “Look at everything it is doing for us, allowing us to become.” She insists, “Love, Your Grace, conquers all.”

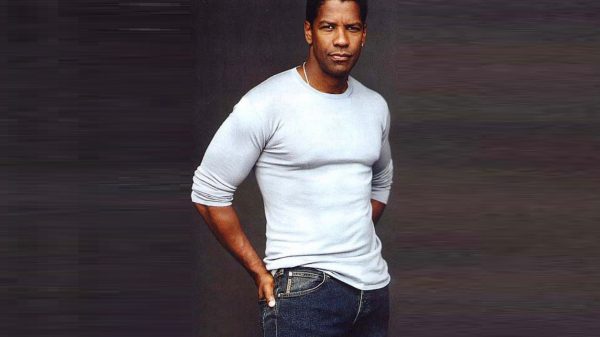

Appearing in the fourth episode of “Bridgerton,” the first series produced by Shonda Rhimes as part of her powerhouse Netflix deal, this conversation between the show’s main Black characters is the first explicit mention of race in a story that revolves around the duke, a Black man named Simon Basset (Regé-Jean Page), and his passionate courtship of Daphne (Phoebe Dynevor), the eldest daughter in the wealthy, white and titled Bridgerton family.

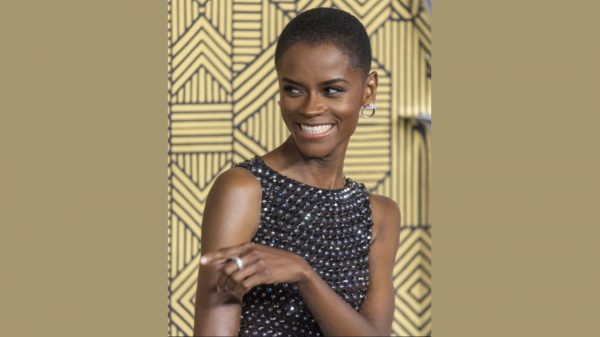

The show’s casting diversity is its most immediately striking quality, not just in Black aristocratic characters like the duke and Lady Danbury, but also in the entrepreneurial Madame Genevieve Delacroix (Kathryn Drysdale) and the working-class couple Will and Alice Mondrich (Martins Imhangbe and Emma Naomi). All of them are central to the complicated social caste system that make up the show’s version of early 1800s London.

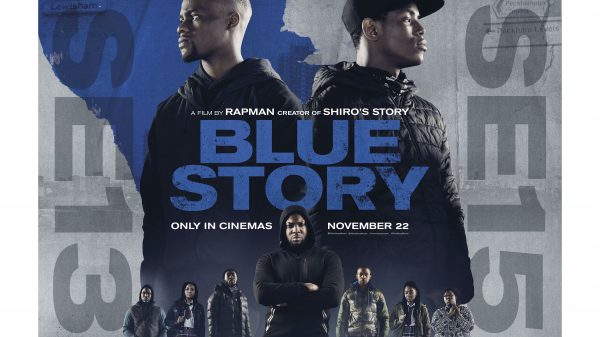

Bridgerton” is not Rhimes’s first dalliance with a multiracial cast in a British period drama. In 2017, she produced “Still Star-Crossed” on ABC, a story that began after the deaths of Romeo and Juliet and focused on their cousins Benvolio Montague and Rosaline Capulet, who were forced to marry in order to heal the family rift. Though Benvolio and Rosaline are intentionally cast as a interracial couple, race was neither a point of contention nor grist for social commentary. Instead, viewers were asked to suspend our contemporary racial perceptions in order to accept the colorblind Verona of the past. (This strategy, among others, was largely unsuccessful — “Still Star-Crossed” was canceled after only one season.)

In contrast, the characters of “Bridgerton” never seem to forget their blackness but instead understand it as one of the many facets of their identity, while still thriving in Regency society. The show’s success proves that people of color do not have to be erased or exist solely as victims of racism in order for a British costume drama to flourish.

Chris Van Dusen, the “Bridgerton” showrunner, was a writer on Rhimes’s “Grey’s Anatomy” before going on to be a co-executive producer on “Scandal,” a show that both recognized but did not entirely revolve around the interracial tensions of Olivia Pope’s romantic relationships. Applying that same approach to his adaptations of Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton novels, Van Dusen places us in an early 19th century Britain ruled by a Black woman, Queen Charlotte (Golda Rosheuvel).

“It made me wonder what that could have looked like,” Van Dusen told The New York Times in a recent feature about the show. “Could she have used her power to elevate other people of color in society? Could she have given them titles and lands and dukedoms?”

Such a move pushes back against the racial homogeneity of hit period dramas like “Downton Abbey,” which that show’s executive producer, Gareth Neame insisted was necessary for historical accuracy. “It’s not a multicultural time,” he said in a 2014 interview with Vulture. “We can’t suddenly start populating the show with people from all sorts of ethnicities. It wouldn’t be correct.”

“Bridgerton” provides a blueprint for British period shows in which Black characters can thrive within the melodramatic story lines, extravagant costumes and bucolic beauty that make such series so appealing, without having to be servants or enslaved. This could in turn create openings for gifted performers who have avoided them in the past.

“I can’t do ‘Downton Abbey,’ can’t be in ‘Victoria,’ can’t be in ‘Call the Midwife,’” the actress Thandie Newton told the Sunday Times of London in 2017. “Well, I could, but I don’t want to play someone who’s being racially abused.” She went on, “There just seems to be a desire for stuff about the royal family, stuff from the past, which is understandable, but it just makes it slim pickings for people of color.”

For all its innovations, “Bridgerton” has its own blind spots. I found it strange that it is only the Black characters who speak about race, a creative decision that risks reinforcing the very white privilege it seeks to undercut by enabling its white characters to be free of racial identity. But at least it’s a start and we applaud Shona for bringing positive colour images into our imagined past.