With the rise of social media, revolutions such as the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, and a more urgent sense of social activism in the air, can comedians still get away with making overly-offensive jokes? Nicole Vassell looks into why it’s no laughing matter

We all need to laugh. With the news cycle channelling sadness into our phones around the clock and non-stop political dramas all over the world, we need some respite in the form of unfiltered joy.

And when times are low, there are few things I like more than to find a new comedy special to indulge in – an easy hour or so where my only job is to literally relax, and have a laugh. To me, it’s healing – and when it interrupts a spell of stress, or personal anxiety, I daresay it’s an act of self-care. Because I enjoy comedy so much, over the course of 2018 I’ve been making an effort to venture out into the real world, and enjoy some jokes told in the immediate atmosphere – a live show, where you can see how the comedian feeds off the energy of the crowd, and how they’re able to manipulate the mood of the room with just a few words.

However, back in January, I saw an internationally known, black male comedian tell a joke concerning the #MeToo movement, with people speaking out about sexual abuse. Instead of making the abuser the target of his joke, the comic did the opposite – saying that he didn’t have any ‘attractive’ women working backstage, as he didn’t want to run the risk of becoming the next man with his head on the entertainment chopping block. Using words to the effect of: ‘the only women working for me are fat, ugly bitches,’ he delivered his punchline to smatterings of laughter throughout the arena audience. Though I wanted to enjoy the show as normal, that cursed line ended up souring much of the minutes to come. Looking over at my friend, in the seat beside me, it was clear I wasn’t alone in this feeling of tension.

‘Why did he make a joke about that? That’s not funny, surely?’

Not long after that, I got around to watching Dave Chappelle’s Netflix comedy specials from late 2017, in which the revered comedian makes a long gag with transgender people as the punchline – one of the moments that jumped out in particular dealt with the hypothetical situation of a trans woman ‘tricking’ a cisgender [biologically male] man into sleeping with her. Chris Rock, whose stand-up special Tamborine, debuted on the streaming platform earlier this year, used a slur targeted towards gay people, as well as making jokes about prison rape that could’ve easily been in a set 20 years prior. Oh dear.

At an earlier point in time, I might have heard these jokes and not thought much of them, depending on the reaction of the rest of the room. If everyone was guffawing, it must be alright, right? But now, as an adult consumer of these comedy products in 2018, I no longer have the ability, nor desire, to gloss over jokes that are more than simply being controversial, or playful.

In a time where victims of sexual and domestic abuse are being encouraged to come forward, it’s punch-lines like the live comedian’s that set us back further than ever – it contributes to a culture that makes it difficult for survivors to have faith that their stories will be believed, especially if they’re ‘fat and ugly’, or if their abuser is a rich, famous man. Jokes like Chappelle’s insinuate that there’s something funny about the mere existence of trans people, as he’s finding a joke in the harmful idea that having a relationship with trans person is something to be embarrassed about.

It’s not that these things should have ever had people rolling in the aisles, or were previously more ‘okay’ – but with my eyes wide open now, it’s a step in the wrong direction to see the same victim-blaming, body shaming formulas being used again to provoke the same, dehumanising jeers from a paying crowd. It’s especially disheartening to see these behaviours coming from the likes of prominent black male comedians, who are in fact ‘punching down’ at the experiences of the very people most likely to have their backs in instances where they face oppression.

This isn’t to say that there isn’t space for contentious content in a comedy set. A lot of humour can come out of surprising the audience with something shocking, and not everyone can be satisfied with every joke – a pinch of salt is always required, before viewing. But surely there is a line between being playful, and being toxic?

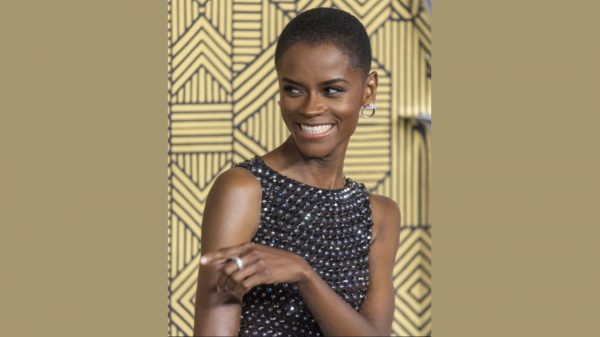

‘Am I being a stick in the mud? Am I “too sensitive”?’, I wondered, ‘Or does the comedy industry have a right to do better with their jokes?’ I spoke to comedian Judi Love, to see what her opinion was from the stage side of this equation. Having worked in comedy for over five years, Judi has seen her fan base grow and grow – by making short, relatable videos for social media, as well as hosting live shows, and presenting engagements as well. In her time working in, as well as consuming, comedy, she’s carved out an act that tries to poke fun at reality, by putting a spotlight on ignorance in society, instead of continuing the cycle.

Judi explains: ‘Some [comedians] will struggle in this moment of “being woke”, or “PC”; for me, I try to touch on subjects that are real to me, and that I experience.’

From her perspective, there’s been a tangible change in how audiences react to offensive jokes – while some provocative lines may have gone unchallenged in the past, things are much different now, with disgruntled fans standing up in the crowd in protest at a joke gone wrong.

‘People are much more opinionated because they have platforms to be opinionated on, whether it’s Twitter, or Instagram, and it translates to the live shows… before, people would feel as if their one voice was not enough. Now, they know their one voice can do a lot, they’re thinking, “There are many more people that will stand with me – I can Tweet about this, record this and it could go viral.”’

Admirably, Judi is concerned with how her words will be received not only in the current day, but in the future: ‘I try to think ahead, and I think – in my sets now, would I be able to do that in a year’s time? How would that affect someone?’

Talking about a joke she has, in which a family member tells their Jamaican granny that she’s gay, Judi makes the joke not about the gay relative, but about the surprising way this changes the family: ‘You spin it, like: “Maybe I need to come out, because she gets better treatment than me from Mum!” There are a lot [of comedians] that cannot come out of that [habit of ‘punching down’], and it will affect their comedy, because people will not stand for that now.’

By nature, comedians want to make people laugh – but no-one who’s already lacking in societal privilege wants to feel as if the whole room is against them, yet again. It’s clear that it’s possible to be funny, without being intentionally, and harmfully problematic. Time is moving forward, and the jokes have to follow suit, or even lead the way, else we’ll come to a time where offensive comedians are no longer relevant – and they’ll have gone too far to return back to the spotlight.