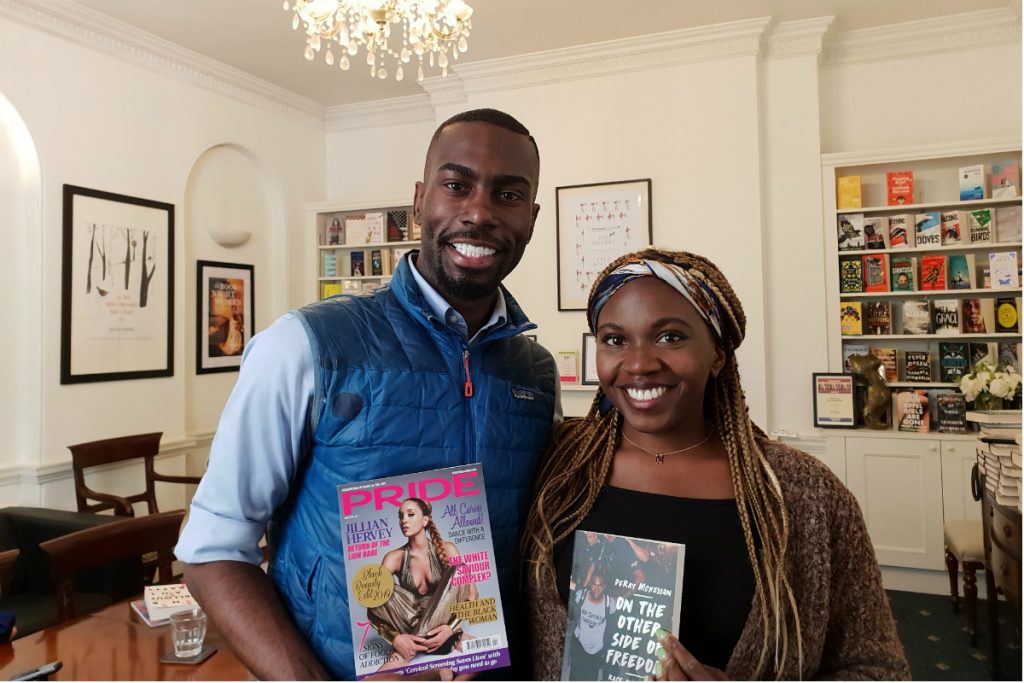

We speak to the Black Lives Matter advocate about his life, five years after the Ferguson protests, and his new book

In the past few years, there has been a new wave of people advocating for justice where they see it’s in jeopardy. From raising awareness online, to contacting their local representatives to physically marching in the streets, there’s an energy in the air that is calling people to action.

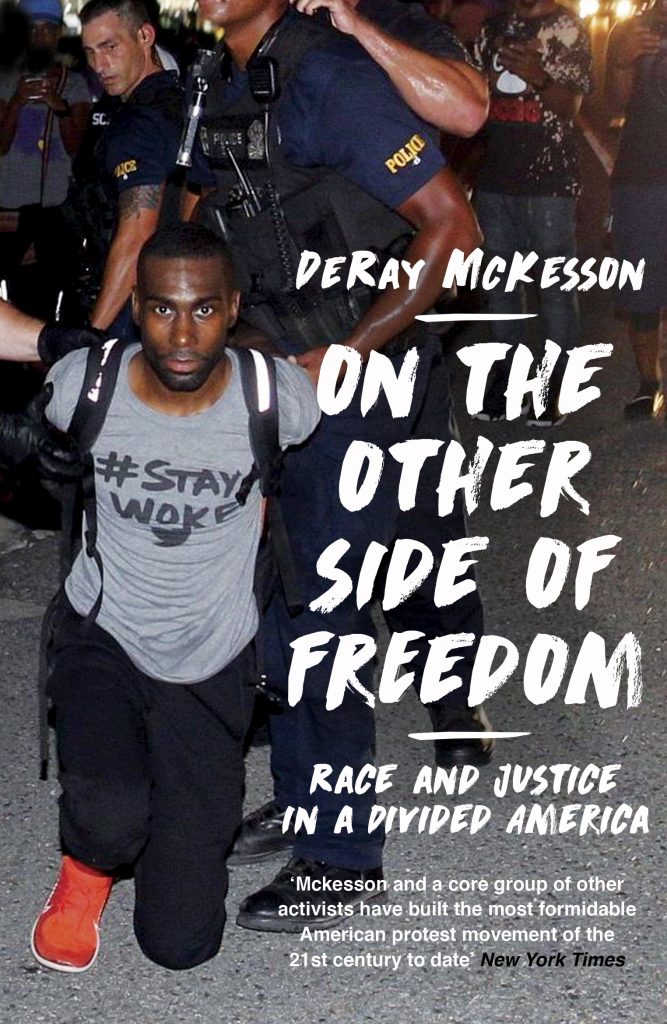

DeRay Mckesson is someone at the forefront of social justice in America, and through his years of effort in bringing light to police brutality, he’s been many people’s entrypoint to an urgent struggle. His new book, On the Other Side of Freedom: Race and Justice in a Divided America, details his journey to becoming a full-time activist, and some practical things he’s learned along the way.

‘I didn’t want it to just be a memoir: I wanted it to also have some lessons in it, because I think about all the things I wish I had when we were in the street,’ he explains during our London interview.

With hundreds of other protesters, Mckesson spent a total of 400 days marching in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri from the summer of 2014, galvanised by the killing of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown by police officer Darren Wilson, and the subsequent decision not to indict Wilson for the fatal shooting. In August, September and October 2014, standing still for more than five seconds was an arrestable offence, meaning that protesters were constantly on the move.

Mckesson, who left his full-time job as a teacher in Minneapolis to protest in Missouri full-time, first gained widespread attention through Twitter. At a time where the social media site was important, yet not as much of a widely-utilised part of news reporting, his tweets stood out as they came directly from the frontlines of the action. Through his tweets, countless numbers of people got an insight of what was happening there, as it was happening.

The book, filled with in-depth tales of protest and personal life, looks at his experiences during these times. Published in America back in 2018, its release in the UK makes five years this summer since the protests began, and five years since he’s been one of the loudest voices for addressing police brutality and disenfranchisement of black Americans. All the way through the book, there’s a constant thread running through it, on the idea of hope. It’s something that’s needed now in a time when we’re constantly bombarded with notifications on how the world is turning over, be it through news push notifications on our smartphones, getting hit by negative headlines while scrolling through social media, or through the more traditional channels of newspapers, TV and radio.

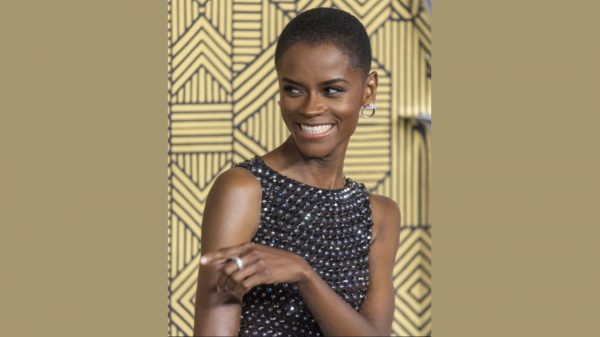

And meeting Mckesson in person, you get the sense of someone whose body is coursing with positive energy, full of ambition to do his part in righting the wrongs that have plagued marginalised people for generations. To this day, he still wears the same blue vest that he wore on the streets, as a constant reminder of the work that’s gone into the cause, and what’s still left to be achieved. Yet, this doesn’t mean that this faith in the future doesn’t get tested.

‘My hope definitely gets challenged; recently the past few weeks have been like, “What is happening? What’s going on in the world?”’ he says. ‘What keeps me hopeful is when we say the system is broken, and people say: “Oh no, it was designed to be like that”. My takeaway from that, is that all this is designed. People made this up, and because of this, people can make it better.’

Despite the belief that things can change for the better, however, Mckesson is hesitant to claim that things have gotten that much better in the time since the Ferguson unrest, and a general renewed interest in vocalising injustices in the world.

‘We have changed the conversation about race and justice, right?’ he begins. ‘But the outcomes have not changed in a way to match the change in conversation. Having the conversations doesn’t always mean the outcome has changed – and if there’s anything I worry about, I worry about that. I think the internet has confused people to believe that they are one and the same, and they are not. I’m in a lot of rooms with people who, while their rhetoric is great, when you’re like, “So what do we do?”, their response is like, “I don’t know.” We actually have to have some systemic analysis, an inkling of a plan to change the outcome. Us talking about it is the beginning, but it’s not the end.’

‘I don’t wanna be the exception to your hate; I want you to actually change.’

As one of the first people that comes to mind as someone dedicated to ‘fighting the good fight’ in America, Mckesson has gained celebrity status, seen through his attendance at A-List gatherings, and being a part of an exclusive, 10-person club of people Beyoncé follows on Twitter (a fact that rolls off the tongue). Early in the book, he mentions an interaction he had where he was being served legal papers, and then immediately asked for a photograph. When asked what it’s like to straddle this line between celebrity and community activist, he admits that although people might see him as a famous person, he hasn’t lost sight of his goal.

‘People will see me with “Enter Celebrity Here”, and think that it’s my life, and that that is all I do. What they don’t realise is that in every one of those rooms, probably to the chagrin of the actual celebrity, I’m always pitching some idea. “Have you thought about what the police are doing, or the racial wealth gap…”’ he trails off with a laugh.

‘Me being more visible is only a win insofar that I can use the visibility to help the work. What makes it hard is that I’m not always able to talk publicly about those conversations, because it can violate the trust in that space. It’s this weird thing where I think people would like me to talk about it publicly all the time, but then that feels like a performance and that’s weird too – but I try to think about it all and figure out how to use it for good.’

With over one million people following him on Twitter, Mckesson’s reach is large, and as a black man who is also gay, he’s someone who stands at the intersection of battles that need people’s support. However, he’s experienced pressure from the groups who are not yet able to reconcile various injustices at once.

‘I wish I thought they improved,’ he says. ‘I think I’m the exception, not the rule. A lot of people say they’re homophobic, but they like me. I don’t wanna be the exception to your hate; I want you to actually change. There’s definitely a whole slew of people who will say that they are not homophobic but ‘need me to focus’ – focus on the issues around being black, and not ‘get distracted’ about the issues about being gay. To some gay people, I’m not gay enough; they feel I need to be more publicly intense about my statements about queerness.

‘Five years in, I’m committed to a set of issues around activism about queerness – I’m obsessed with structural changes, like what does it mean to change the outcomes around HIV and Aids? What does it mean to end homelessness for gay kids? What does it mean to make classrooms safe for gay and queer kids? I wish that it didn’t have to be an either/or – that I’m for black people, or for gay people; [I wish] that people could understand that we’re complicated, complex people who can fight for two things at once.’

With this book, and the continued hard work, here’s hoping that one day that’ll be a reality.

On the Other Side of Freedom: Race and Justice in a Divided America is out now