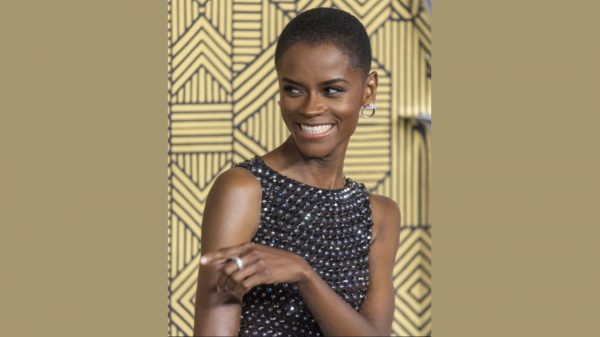

We speak to Marvyn Harrison, the founder of a podcast and social forum that helps black fathers all over the world connect in a unique way

On Father’s Day 2018, advertising professional and dad-of-two Marvyn Harrison combined a number of fellow black fathers in a WhatsApp group with the simple aim of highlighting them for the positive role they played in their children’s lives. In case his peers weren’t feeling as appreciated they deserved to feel, on this day, Marvyn was determined to let them know that they were seen.

‘I didn’t have a father around, and my wife’s father passed away when she was young, so Father’s Day has never been a big day in our calendar,’ he tells me. ‘My wife, Nina, does a really good job in the morning, in terms of getting the kids together with cards, but after midday we’re just sitting here, watching TV as usual. So on that day, what I wanted to do was give everybody a second wind, and really let my peers hear from another man: I appreciate you.’

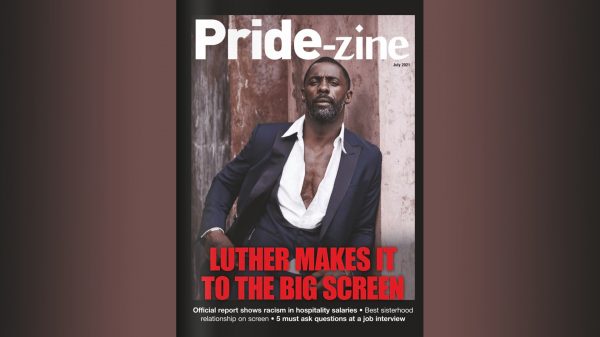

Little did he know, this opening message would form the start of a movement that now reaches members from London to New York to South Africa, who through social media have daily contact about the various challenges and triumphs that come along with being a black father. It was the start of Dope Black Dads, which he describes as: ‘a resource to our community; we’re increasing our understanding, collectively, of what parenthood means for black men, and we’re moving the needle forward.’

After the initial responses of thanks and gratitude to Marvyn’s Father’s Day shoutout, it didn’t take longer than a day for important conversations between the dads to begin sparking, borne out of the fact that the group was such a specific, yet up until then, a missing kind of arena to discuss deeper issues on a wider scale.

‘One of the first conversations that was particularly meaningful was about kids and education; one of the dads was promoting homeschooling as an alternative for the exclusion problem we have for black children,’ Marvyn says. ‘So we were like: “Okay, never thought of that – how does it work?” And he broke down his experiences with it – affording it, balancing the responsibilities with his wife… We started talking about finance, investing money – these are taboo subjects that most men don’t talk about, because of pride, ego, or lack of knowledge. But it was really beautiful to hear men talk about their most personal aspects of their lives: how they’re structuring their homes with their wives, how they have a democratic process to make decisions – it was beautiful.’

‘They say being a dad means being the one creating discipline and structure – but where are examples of the dads that cry at their child’s birth, and really absorb these moments of being a father?’

Marvyn knew that in these conversations were something that was not only cathartic, but valuable to all involved, and as knowledge of the WhatsApp group spread, and more and more fathers were interested in joining, they transferred their interactions to the more manageable platform of Facebook, and found that a network spanning the globe was beginning to form. Where there are multitudes of platforms and real-life organisations for mothers to connect, the promotion of a father-specific forum isn’t as popular; and even before the formal beginnings of Dope Black Dads, this was something that Marvyn had noticed a big need for, but didn’t exist. For him, this lack of attention to black fathers meant that there wasn’t a consideration of black men having emotional connection to their families:

‘If we’re left out of the conversation, people start to look at other ways of building family, because they don’t feel like black dads are needed,’ he admits. ‘I think we celebrate the idea of single black motherhood way more than we celebrate a single unit. When there are real needs for it, we absolutely should – my mum raised me that way. But at the same time, when there are fathers there, we don’t celebrate them, or hardly ever talk about them… they just disappear.’

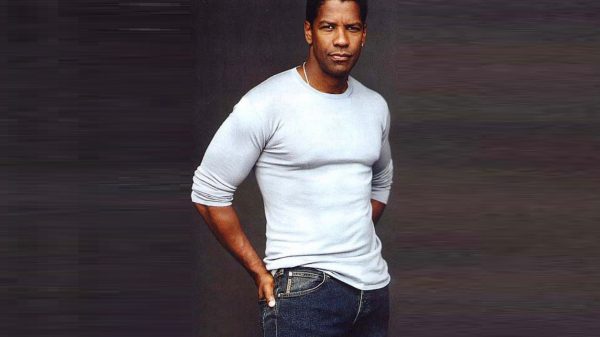

When it comes to media representations of black fathers, there’s something of an ingrained assumption that they’re more absent than those in father roles in other races – or, if they are in their children’s life, perhaps they’re not as hands-on, or as engaged as they could be. Though this is the experience of some, it’s far from always being the case, and since becoming a father to three-year-old son Blake and daughter Ocean, one, Marvyn has quickly reconsidered his conceptions of what fatherhood is – and he’s found the portrayal of black dads up until this point as largely insufficient to the realities that he and his peers have felt.

‘I’ve always wanted to be involved with raising my kids, and I’m lucky: the way my marriage works, my wife has always left the door open,’ he says. ‘But I’m not operating off of muscle memory; this is a very conscious thing, being a father, one: because my father wasn’t around, and two: the father roles we do see are the ones who are just there to make money and discipline.

‘You don’t often get to see the other part; where you’re talking, and playing, and loving and crying. It’s very emotional as a process, becoming a father,’ Marvyn continues. ‘There are so many things that you think about, and you have this feeling of true love for someone that you actually made – all of those emotions get minimised when you see them documented in media. They say being a dad means being the one creating discipline and structure – but where are examples of the dads that cry at their child’s birth, and really absorb these moments of being a father? We’re not shown images of fathers being insecure in what they’re doing – that narrative doesn’t get celebrated as much as the role of the disciplinarian, wise, Uncle Phil archetype.’

In the Dope Black Dads forum, there’s a great variation of parenting choices expressed – whether you’re an ‘Uncle Phil’ kind of father or not – and there’s warm, open and often funny discussions about topics from the stereotypes that get attached to black men, to important ongoing conversations about consent, homophobia, religion and parental trauma. There’s no limit to what’s discussed – if it’s something that’s on a member’s mind, the floor is always open, and there’s always the opportunity to learn from the words of another.

‘In other WhatsApp groups with other friends, we may talk about one of those issues, with one person at a time, but we’d never have full discussions like this,’ Marvyn admits. ‘It normally turns into jokes about football; it never gets granular, or stays specifically about these other topics. I think of Dope Black Dads as a mobile safe space that’s always with you, whenever you need it, whatever the issue is, as long as it’s personal, we accept it in our space, and there’s zero judgement.’

Since the launch of the podcast in October 2018, Dope Black Dads has been even further established as a necessary resource for father figures who need others like them to connect with – as well as those who don’t fit into their categories, but want an insight into the truths that black men experience but often don’t feel comfortable sharing. With in-person meetups and park days in the calendar, as well as the group gaining coverage in national media, the movement is going strength to strength. This June marks a year since the seed was first planted, and if this is what they’ve managed to achieve so far, it’s all the more exciting to see just where they’ll go next.

For more info, head to dopeblackdads.com.

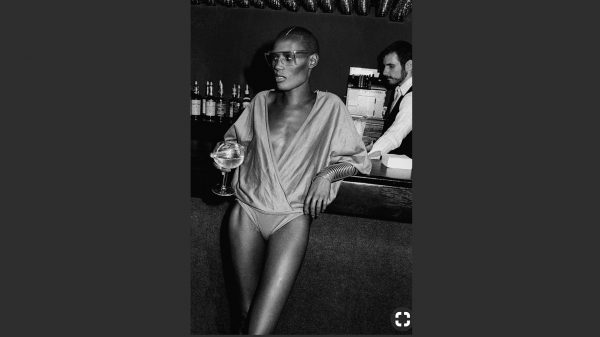

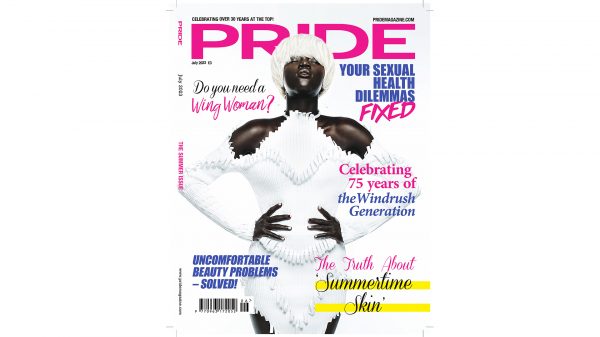

All images by Sarpong Photography