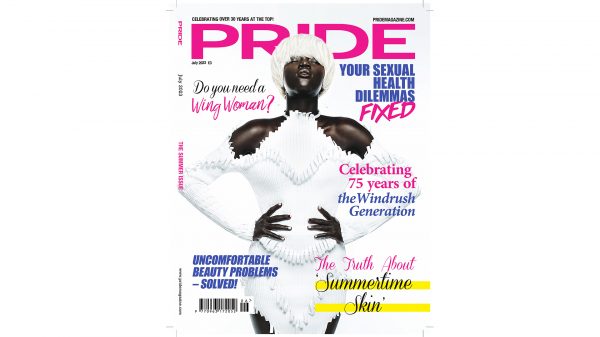

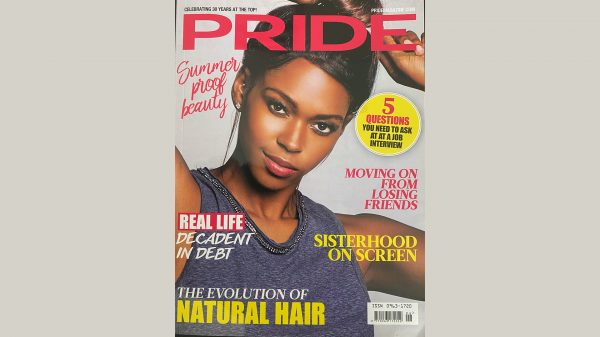

‘I was about 15. I actually hadn’t come out as trans yet. But I’d be in the salon, getting my hair done, and I’d look at these women, like Mary J Blige and Naomi, and I’d love them so much. And now, it’s my turn!’

Munroe Bergdorf is talking about her teen years, reading Pride, and admiring the stars on the front cover – and now, in a happy full-circle moment, she’s now one of those women herself.

‘It’s crazy, right?’

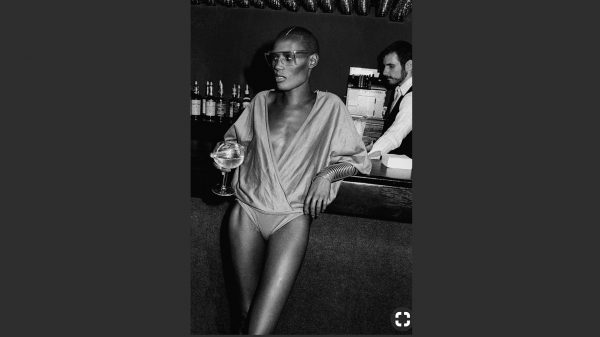

To say that 2017 has been one heck of a rollercoaster for Munroe would be one heck of an understatement. Later on in our conversation, she’ll tell of a recent Gucci party she attended with friend, and fellow trans model Hari Nef. At one point, she was stood with Naomi Campbell behind her and Leonardo DiCaprio in front – and was truly star-struck.

‘I didn’t know where to look!’ she exclaims, eyes wide. ‘I don’t even get like that when it comes to celebrities – but looking around and seeing Naomi and Leonardo? That’ll do it.’

Though the social activist and model had been known (especially in LGBTQ+ circles) through her DJ work and her vocal takes on injustice on social media for quite some time, the final third of 2017 has propelled awareness of the 30-year-old to new heights. In August, it had been announced with much excitement that she was the newest ambassador for L’Oréal; and as the first black, trans model to lead a British beauty campaign, it was a moment for the history books.

With features in major publications coming in thick and fast, this should have been a landmark moment – bona fide proof of the motion toward true diversity within the beauty industry, which has historically excluded those who exist outside of white, cisgender [those whose gender identities match their assigned sex] beauty standard.

However, the joy wasn’t to last long. In a trend that has become very popular in more recent months, Munroe’s social media history was brought to the attention of the public via a massive news organisations – in her case, it was by way of a tip-off from an ex-classmate from her University of Brighton English degree.

But while most shamed celebrities face admonishment for harmful quips and ignorant slurs unearthed from many years prior, Munroe’s fateful words were only taken from a passionate Facebook status against racism from only a month prior. It read:

‘Honestly I don’t have energy to talk about the racial violence of white people any more. Yes ALL white people.

‘Because most of ya’ll don’t even realise or refuse to acknowledge that your existence, privilege and success as a race is built on the backs, blood and death of people of colour. Your entire existence is drenched in racism. From micro-aggressions to terrorism, you guys built the blueprint for this s***.

‘Come see me when you realise that racism isn’t learned, it’s inherited and consciously or unconsciously passed down through privilege.’

Written in reaction to the white supremacist and ‘alt-right’ riots in Charlottesville, Virginia, Munroe explains that the status was her explaining of how racist structures in society have continued to disadvantage black people, and the ingrained effects of systemic racism on everyone’s behaviour.

However, the story was quickly stripped of nuance, and widely reduced to ‘trans model in race riot’ by many, with critics deeming her racist – a cruel twist of irony, since her intention was to call out the widespread existence of racism in the first place.

‘It basically looked like I was just slagging white people off,’ she sighs, exasperated. ‘It became worldwide news.’

From faceless trolls sending horrific threats online, to being baited live on morning television with a known antagonist, Munroe had all the eyes of the global public on her. L’Oréal announced it was removing her from the campaign within days of her status becoming public, leaving the floodgates open for even more abuse.

‘It was a really weird situation to be in, and to be constantly inundated with notifications… I mean, I’ve never seen my phone erupt like that. I was waking up in cold sweats, because when something like that happens, you think it’ll never stop.

‘It kept on like that for a solid week. It’s still going, but not as bad now. I can just focus.’

When we meet for coffee at a cool Islington brunch spot, it has been over two months since the media storm that ultimately changed Munroe’s life. Despite floods of support from people online – many of them black women, she points out – plenty of hot takes on the situation had stripped her sentiment of context, and the turned the title of ‘racist’ threatened to be turned back on her.

She was also dropped from three other campaigns before they’d even been announced – in her words, they were ‘playing it safe’ in order to secure the support of those who have the most money. Though the heat has tapered off, going through a public debate without a publicist, or a manager to take the brunt off must’ve been incredibly difficult. How on earth did she get through it all?

‘God knows,’ she shakes her head. ‘I always say now that I’m a lot stronger than I thought I was; I think we all are. And it took a situation like this to summon the energy and realise that.

With her words having been reduced to the controversial soundbite ‘all white people’, in hindsight, is there a part of her that regrets the way she said it?

‘No,’ she says firmly, barely letting the question finish. ‘I don’t think that every single white person is racist, obviously, but you have to be conscious of the fact that we’re all born into social structures. You can’t just assume that you’re not something, or not a part of something, just because you don’t like it.

‘Racists don’t like to be called racist – and many people get lost in the idea that it’s just a matter of not saying the N-word. It’s gatekeeping, it’s microaggressions – it’s all a part of it. And if we don’t act out against them, and push back, then we’re just playing into the hands of oppression. As much as it’s provocative, it has to be.’

The cross of speaking out about race as a black woman is a heavy one to bear – and she’s continued to use her social media platform to address instances of injustice. However, through all the stress of skyrocketing to fame, Munroe is quick to point out the positives that have come from a tough situation. Having now collaborated with brands such as Illamasqua and Missguided since the storm, she’s been able to pursue her love for fashion and beauty on a wider scale. On a recent trip to LA, she shot a number of upcoming campaigns, as well as filming videos for BuzzFeed, and teaming up with model and friend Isis King. Munroe also was invited to Cambridge Union to speak about intersectionality – the overlapping of different social categories such as race, class and gender, and how it creates dependent systems for discrimination. Where some windows glued shut after she raised her voice, doors of opportunity have swung open.

‘Everything in my life is magnified now,’ she admits. ‘I was modelling before, and doing amazing stuff – but this has made everything so much bigger. I have more direction – and I’m careful. I get asked to do things now that I’ll turn down if it feels…’

Gimmicky?

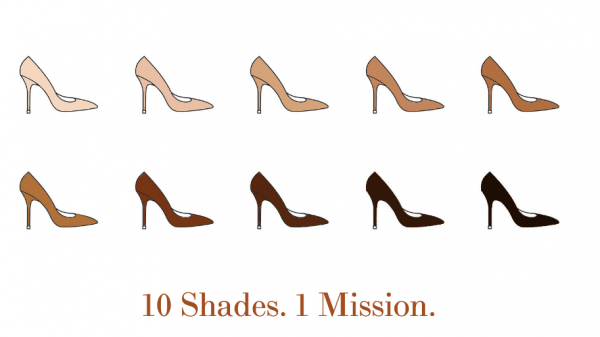

‘Yeah. There’s a big difference between tokenism and diversity, and a lot of people think that diversity just means plopping a black person in front of a camera. There needs to be all sorts of representation at every level – people of colour behind the scenes to call things out.’

A year ago, Munroe couldn’t have imagined the professional developments that have occurred – and much less when she was that young teen, reading Pride in the salon chair. She grew up on the border of Essex and Hertfordshire with her white English mother, her black Jamaican father, and a brother, four years her junior. She describes it as a lucky childhood, having attended a ‘good school, in a good area.’ However, she and her brother were the only black children in school – which inevitably contributed to her awareness of race in Britain from a young age.

And of course, growing up as a trans child in the Nineties wasn’t easy – with minimal access to information, and a lack of role models to help explain her feelings, it was a confusing time.

‘I was a transgender child, but I didn’t know what that was at the time, because there wasn’t any information out there. I’m lucky that I wasn’t in a bad household; I had two parents who didn’t always get everything right, because whose parents do?’

It wasn’t until she was 18 that she told her first person that she told her first person that she was trans. It would be another six years before she decided to transition, and start taking hormones – which she describes as ‘basically going through another puberty.’

Though cautious not to give away too much about her family life, Munroe admits that there were some growing pains between herself and her loved ones during her transition period.

‘It took a long time to acclimatise. Me and my mum fell out for a long period of time. I think she was worried about how the world would perceive me. It wasn’t her own prejudice, I don’t think – it was a lack of understanding, as if she thought it was just going to be a phase. I think she was scared that I was going to turn up one day not being the same person she gave birth to.’

For this reason, she also invites the parents of trans and queer children to speak to her with any questions. Though becoming an advocate for trans youth and black women wasn’t necessarily part of the plan, she’s now something of a role model to many who cling onto her every word – because she didn’t have anyone to turn to, herself.

‘I never saw myself as a role model up until now – but I feel like I’d be doing them a disservice if I wasn’t there for them. Kids literally message me to tell me things like what grades they get on their homework! I’m not perfect so I say I can’t give too much advice, but I say if you’re feeling alone, or like you want to harm yourself, don’t do it. I’ll listen.’

As much as she’s passionate about advocating for blackness, and trans identity, and womanhood, I have to ask: doesn’t it get exhausting, having so many people suddenly placing their hopes of ‘wokeness’ onto her shoulders?

‘Yeah, but I’m learning to balance it. I need to recognise that my own happiness will help me to give love and happiness to other people. Things like giving myself time and space to breathe, and to make sure that I have enough time to run myself a bath! I just want to be good to myself so that I can be good for others.’

And Munroe is really someone you want to be good to themselves. Warm, fascinating and fiercely intelligent, she has the rare ability to make the people she’s with feel comfortable instantly; it’s easy to see why young people from all over the world, from Kentucky to Kent, think of her as a big sister. 2017 has pushed her to limits she didn’t know existed – and limits that many of us would never want to be pushed to in our own lives.

Munroe’s strength is to be admired; but too often, black women are expected to be constantly resilient, and denied the opportunity to be vulnerable, and kind to themselves. I’m genuinely glad that when flying the flag for everyone in trouble gets to be too much, she simply says no, and chooses herself.

Towards the end of our chat, I ask Munroe if she’s happy with how things have panned out – and though she’s honest about the pain she’s been through, she’s optimistic.

‘I like how it’s going. How it started isn’t ideal, I had about five breakdowns, and aged about ten years, but it’s okay. I’m really excited about every day.  I am really lucky that I get to channel my energy into the things and causes that I love and care about. I’m doing what I want to do.

I am really lucky that I get to channel my energy into the things and causes that I love and care about. I’m doing what I want to do.

‘At the end of the day, I’m an activist, and this is what I’ve been doing for a long time – and I’m not going to stop. Time and time again, we see the focus of hatred move to different groups – Jewish people, gay people, black people, trans people. Oppression shifts – so it doesn’t matter who’s on the receiving end of it, I’m there with them.’