From Blac Chyna’s skin-lightening backlash, to Spice’s lighter ‘new look’, skin bleaching continues to be a fierce topic of debate. Nicole Vassell reasons that the lion’s share of the criticism should go to an unfair society, rather than the users themselves

The first and only time I came in contact with a bleaching product was back when I was 13. After a particularly nasty fall in PE, I cut my leg badly. While this gave me a (for once) legitimate excuse to sit out of physical activities for the next couple of weeks, it also left me with a trail of unevenly dark brown, randomly shaped scars, stretching from my right knee to two-thirds down my shin. It wasn’t exactly what I, an insecure teenage girl, wanted to add to my collection of physical gripes, so my mum got me some bleaching cream.

An easy purchase from the local Black hair shop, the cream’s instructions told me to apply it to the areas I wanted to lighten twice a day for at least three months, or until I’d seen the change I wanted. Ultimately, this was more of a task than I realised, and I gave up after about a fortnight – and as a result, I still have the souvenirs of that fall to this day.

However, there are plenty of people who haven’t been as lacklustre in their bleaching routines as I was – nor were they trying to rectify the remnants of an injury on their skin. Many ‘bleachers’, of all ethnicities, are instead trying to modify much more by applying the product all over their body, with their only ‘blemish’ being the natural colour of their skin – and it’s heartbreaking.

Controversial rapper Azealia Banks is one of the first people that come to mind when it comes to a public figure involved in this issue. Naturally of a darker complexion, she received a lot of criticism for lightening her skin colour with the help of ‘brightening’ agents. In the years since, she’s argued that she only did it in an effort to fade some hyper-pigmented scars – yet that hasn’t stopped her from making skin bleaching a part of her creative legacy; in 2018, she launched a range of soaps through her Cheapyxo skincare brand, specifically for making genitals lighter.

Following this, people revoked their support, waning as it were, from Banks, deeming her a ‘sellout’ with a bad case of anti-blackness. And honestly, I was right there criticising with them: about Azealia and others, I made harsh comments, urging them to do better, and scorning them for not properly appreciating the melanin in their body.

However, while I still believe that a level of disappointment when learning of someone’s bleach adventures is warranted, over time I’ve realised that my ire should be redirected. Rather than putting all the blame on the individuals for changing their skin colour, it’s important to turn the gaze back onto the society that tells them it’s necessary to do so.

In recent history, there hasn’t been a sustained period of time where beauty standards haven’t leaned towards whiteness: be it in terms of hair, facial features, or complexion. And while fuller lips and shapely bums are in vogue now, they receive greatest praise when they feature on the bodies of non-black women – showing that aspects of black physicality is most desirable when separated from black bodies.

Though lighter-skinned people of colour undoubtedly face their fair share of discrimination, there are myriad cases in which lighter skin has resulted in this beauty privilege. For some darker-skinned people, skin bleaching is a reaction to a world in which their beauty isn’t recognised, or their opportunities are diminished by a bias towards whiteness. It’s seemingly a shot at a better social standing, but their actions often result in ridicule.

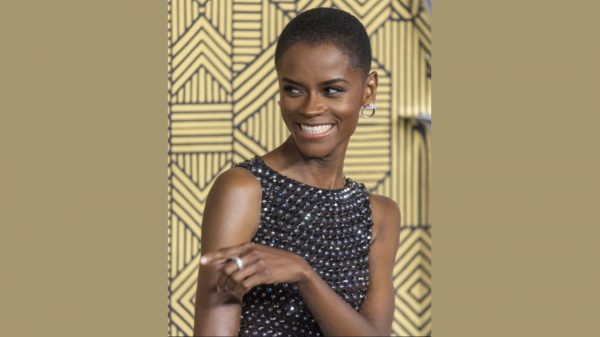

Last month, social media star Blac Chyna visited Nigeria for the first time to promote a skin-lightening product called ‘Whitenicious’. With a name like that, there’s little ambiguity in what the product, for which Chyna is now the face of, is there to achieve – a ‘whiter’ complexion. Though its official line tells its clients that its purpose is to ‘say goodbye to hyperpigmentation and dark spots forever’, its marketing strategy, largely featuring models with very light skin, suggests otherwise. Its founder, Cameroonian celebrity Dencia, has also dramatically lightened her skin tone over the years.

‘77% of women in Nigeria are reported to use some form of skin-lightening product on a regular basis’

What’s most upsetting about this particular case is the fact that the product, and ones like it, are so prominent in a country that’s predominantly black, and with a documented issue when it comes to altering skin complexion; according to the World Health Organisation, 77% of women in Nigeria are reported to have used some form of skin-lightening product on a regular basis. Even in the very continent from which Black people came from, their natural skin isn’t seen as ‘enough’. For exploiting this unfortunate state of affairs, Dencia and Blac Chyna are part of the problem, as well as being victims of it.

In October, dancehall artist Spice drew direct attention to colourism (preferences towards lighter skin) in the music industry, with the elaborate stunt of ‘going light’ for a few days. Surprising her followers, she erased all previous images from her social media accounts, and posted some new photos with a blonde wig and much lighter skin. Though some fans were puzzled and gravely disappointed, Spice (real name Grace Hamilton) soon revealed that it was all a ruse – she hadn’t really lightened her skin; she just wanted to draw attention to the message in her new song ‘Black Hypocrisy’.

She sings: ‘I get hate from my own race, yes that’s a fact, because the same black people say I’m too black, but if you bleach out your skin dem same ones come ah chat’ – which stands as a succinct analysis of the entire issue.

Dark-skinned representation is better now than it has been, but it’ll take more than a few prominent roles in media to reverse generations of implicit bias that places proximity to whiteness as the goalpost for attractiveness – while also shaming those who do what they can to reach it. As much as we can repost images and messages that say ‘love your dark skin’, action is what’ll make the message really go further than the surface.