Conserving collections at the National Trust is about enabling path ways of understanding and connection with our collections. Language is an important way we communicate that knowledge and our intentions to connect with people.

In the wake of the social upheaval of 2020, it became clear that we needed to ensure the language used to describe our collections online was respectful to communities of colour. When our internal collections information was put online ten years ago it was released without review, so the existence of antiquated words describing people of colour needed attention.

As a small project team, the most visible changes we made were to the descriptive titles of paintings – usually considered an unchangeable category. However, until the nineteenth century it was not common for artists to give paintings a formal title. Therefore, most pre-nineteenth century paintings in exhibitions or online have given titles describing the subject matter.

Descriptive titles are often the decision of the person who originally documented information about the painting. Our first undertaking required sensitively interrogating those historic language choices.

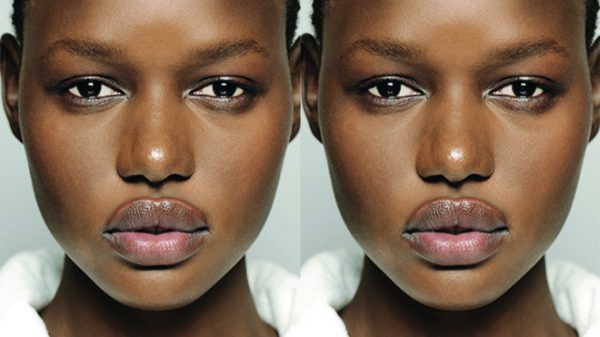

The oil painting ‘Woman in a Red Dress’ (c. 1660-69),attributed to Gabriel Metsu of the Netherlands, is in the Polesden Lacey collection. It depicts a young Black woman wearing a lustrous red dress and a head covering, with a pearl earring. She sits framed in an arched window and is the sole focus of the painting. Many historic Dutch artworks depict Black folks as secondary figures, but this unknown woman is a rare acknowledgement of the diversity of Black presence in seventeenth century Europe.

The painting was historically given the descriptive title ‘Head of a Negress’. A simple change to ‘Head of a Black Woman’ seemed reasonable, but as the project progressed, we began to question why we were only racialising non-white sitters in portraiture.

Thinking through historic word choices led to deep reflectionson the political and aesthetic sensitivities connected to waysart contributes to racialisation. We wanted to understand howlanguage encodes stereotypes and reinforces racial differenceso we could make more informed choices for our artworks.

Removing racial identifiers or historic language describing artis an on-going conversation that will likely evolve. Where a realistic attempt at representing Black individuals is demonstrated, we added a searchable subject online called ‘Black presence’ to help audiences discover these works.

Our considerations around ‘race’ also circled the subjects of enslavement and agency. The misconception that blackness equates to slavery undermines a long history of Black folksliving and working in diverse professions throughout Europesince the Roman Empire.

As European participation in transatlantic slavery solidified, many real or fictional Black attendants were included in portraiture to signal the wealth, prestige, and status of the white foregrounded sitters. These attendants are mostly unnamed and absent from descriptive titles.

Unless there were clear artistic indicators such as a metal collar or chains, we decided not to presume enslavement in our titles. Assuming homogeneous enslavement reinforces a sense of insignificance that minimises the enduring Blackpresence and contributions to national history.

We addressed descriptive titles to appropriately recogniseBlack sitters in portraiture, but we know that simply changing words does not negate historic choices. Throughout the project we documented any derogatory language or inappropriate descriptions internally, as these decisions speak to how organisations are reconciling the changing values of society.

Understanding if ‘Woman in a Red Dress’ is a real person with her own story of agency is complex and requires further research. In time, we want to move beyond language concerns to present a comprehensive understanding of history and representation.

Article Credited to:

Dr Christo Kefalas – Senior National Curator, Global and Inclusive Histories at the National Trust