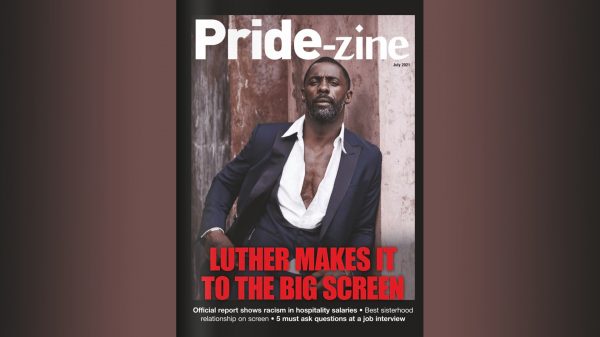

Last year saw national discussions spark up, with regards to gaps in pay between people of different races. Nicole Vassell recalls what’s been found, and what’s left to do

For many readers of this magazine, there will likely be an awareness of the gender pay gap – a maddening phenomenon that refers to a gap in the average salaries of men and women in the same, or similar positions.

However, the past couple of years have alarmingly revealed that there is also evidence of a race pay gap – a gap between the salaries of white workers and BAME workers. Great news for women of colour, right?

According to research published in December 2018 from think tank Resolution Foundation, Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) employees are losing out on £3.2billion a year in wages compared to white colleagues doing the same work. Though it’s something that many undoubtedly suspected, seeing it acknowledged in the form of major studies adds another level of disappointment, and makes it more of an urgent problem in needs of rectifying.

This conversation began in 2017, when the government’s Race Disparity Audit showed widely varying outcomes in areas including education, employment, health and criminal justice between Britain’s white and ethnic minority populations. Prime Minister Theresa May followed this up in October 2018, launching a consultation to see whether forcing employers to report their ethnicity pay gaps can make a difference.

ITN voluntarily published their internal findings, and shared that staff from a black, Asian or other minority ethnic background typically get paid a fifth (20.8 per cent) less than their white colleagues – and when it came to bonuses, the median gap was 50 per cent. Though this information might sting to look at on paper, it’s clear evidence of a pay disparity, and its extent at the very least. When these details go unpublished, it makes the legitimate concerns of employees the equivalent of hearsay, without a cause for it to be solved.

Reasons for why there is a general gap between the earnings of people of colour and white people are varied; one being a lack of BAME workers in high-powered positions. Outside of businesses that specifically have diversity at the forefront of their aim, it’s rare to see people of colour at the highest ranks in the workplace.

In addition, last month a study by TUC indicated that BAME workers are faring worse in the jobs market, with this demographic being one-third more likely to be trapped in insecure work (zero-hours contracts and temporary work) than their white counterparts – surely, a large factor that contributes to the existence of a pay gap.

And though there’s widely published proof of a gender pay gap throughout many industries, black men remain at a disadvantage: a newsletter published on inews.co.uk in April 2019 states that the ethnicity pay gap is growing between BAME and white men who do similar work.

As we approach the halfway mark of 2019, this isn’t something that can continue much longer. Though Brexit continues to dominate the government’s, and the media’s attention, we shouldn’t let this be something that gets swept under the carpet until we forget. The sooner more companies reveal their ethnicity pay gaps, the sooner something substantial can be done to fix it.