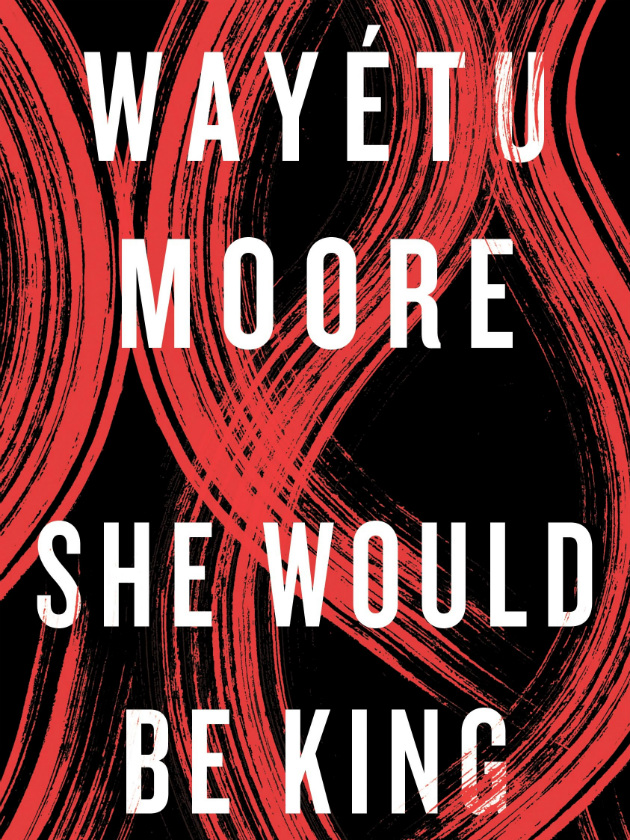

The author of irresistible new fantasy novel, She Would Be King, speaks to Pride

When’s the last time you’ve read a novel about the origins of Liberia, from the perspectives of three supernaturally talented beings? To take a wild guess, the answer to that is probably ‘never’ – which is all the more reason for you to sit up and pay attention to Wayétu Moore’s debut.

Set in the late 1800s, it brings together the stories of three black people at different moments of the transatlantic slave trade: Gbessa, a red-haired, dark-skinned Vai woman from Liberia; June Dey, an American born into slavery on a Virginia plantation; and Norman, a mixed-race son of a Jamaican Maroon woman and a British settler who’d forced himself upon her. Though misfits in their environments, each character has a secret supernatural power that eventually becomes part of their strength in saving themselves, as well as others, in the early years of contemporary Liberia – a West African country that was established as a free settlement for black people in the late stages of the slave trade.

While being an immediately gripping story of that combines real-world history with fantasy, She Would Be King intertwines so much of the African diaspora’s stories, and serves as a reminder of how much our histories link with each other’s, even if the country on your passport differs.

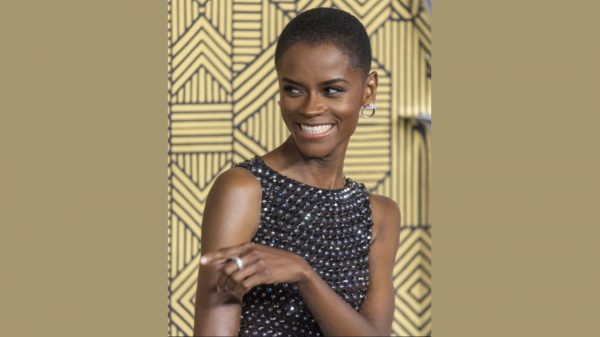

It is also the debut offering of Liberian-American author Wayétu Moore, whose family moved to the United States when she was five as a result of being displaced by the Liberian Civil War. Though she hasn’t moved back permanently, Moore is very passionate about and connected to the culture of Liberia. In fact, she’s also known for establishing the initiative ‘One Moore Book’, a multicultural book publisher aimed at encouraging reading among children of countries with low literacy rates. Moore opened a bookstore and reading centre there in Liberia in 2015 – an achievement she counts among her proudest moments.

We spoke to Moore about her stunning debut, the potential challenges of representing different channels of the transatlantic slave trade, and how fiction can help to inspire change in reality.

Congratulations on She Would Be King – it’s an absolutely stunning read, and so unlike anything else I’ve read before! Before you decided that you were definitely going to explore writing a novel, did you always know that a story about the origins of Liberia was the tale you wanted to tell?

I always knew that I wanted to tell a story that explored this history. Growing up, I rarely heard about Liberia outside of my home, but I knew that it was so close to American history and African-American history that it just seemed like a grave injustice that we were not learning about it. So when I became an artist and began to write, Liberia was the first place my mind went to. Certainly when I decided that I wanted to become a fiction writer and started to explore novels, Liberia was the first place I went to because it wasn’t a story I’d read. I truly believe in that Toni Morrison quote: ‘If there is a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, you must be the one to write it.’ That was something that stayed with me, and Liberia was naturally the first place I went to creatively, because it was absent for a very long time.

Gbessa, June Dey and Norman each have amazing strengths and gifts – yet also find themselves in isolation, and incredibly lonely. Why do they all have loneliness in common?

I have always been a fan of the fantasy genre, and books that champion the supernatural, and something that all of the stories had in common was that the characters did seem to suffer from some isolationism, and that’s what inspired their desire to actually help people, and make sure people feel whole and fulfilled in ways they were never able to. They know how abysmal pain can feel. And so I knew that in order to convince myself of the characters’ willingness to help others, they themselves would have to experience a fair amount of pain and isolation.

Something that’s particularly interesting is that She Would Be King spans different vantage points of transatlantic slave trade – we meet African-American, Caribbean, and West African people affected by it. Why did you decide on this multi-view take?

Liberia has a complex history, because of the identities that comprise the nation. There are indigenous ethnic groups that occupied the region way before the settlers arrived, and then of course, freed blacks and former slaves from America and the Caribbean, who moved to the region from the early 19th century to the early 20th century. I knew that in order to give that history and complexity justice, I needed to fully delve into these other stories, and sort of give all of the groups that comprise the republic, reverence. I wanted to explore the marriage of the indigenous African, African-American and the Caribbean, because these are the cultures that make up what we understand, or at least we understood before the war, as the contemporary Liberian identity.

Did this choice pose a challenge, representation wise, in getting a handle on all the perspectives?

No – I was born in Liberia, raised in the American South, in Texas, and spent my adult years in the northeast, so I definitely have African-American sensibilities. My father, his family is of Americo-Liberian descent, while my mother’s family is indigenous. One of my father’s grandmothers was Caribbean… so already I was exposed to various perspectives and groups. A lot of my research was talking to some of the oldest Liberians I know. My grandmother, for instance, she’s 94, so I was asking her if she remembers stories from when she was a young girl, maybe stories her grandparents had told her, because that was the closest I could get to that period of time – that was something that was important to me. So, I’m from a mixed background, and that contributed to the life of the story.

And finally, there’s an amazing passage in the book that reads: ‘The possibility of rebellion and true freedom in all their hearts. All were mere men. All were powerless but died with raised fists.’ It’s a really galvanising quote. Was writing passages that can inspire action and revolution in the real world an intentional thought of yours?

I hope so. We are in the age of the social movement, where people are trying to provoke change in many ways, and fighting for equality and justice. I certainly hope that the story of Liberia gives a sense of renewal and space to the story of black bodies around the world. I hope that someone can read the book and understand that black bodies in Flint, Michigan are going though something similar as a black body in Rome, Italy, or a black body in Liberia, West Africa, and see the connectedness of a story of turmoil and a form of struggle and perseverance. Liberia is a pan-Africanist story in essence, and I wanted to dissect that in this work.