Before setting out to write this article, the most I knew about Kwanzaa was the little I remembered from childhood reruns of Rugrats and The Proud Family. In these cartoon episodes from the early 2000s, characters Susie Carmichael and Penny Proud respectively were used as vessels to educate viewers about the African-American festive holiday.

As a young black Brit, I thought of it as something exclusive to people over in the States ‒ and since I’d never known anyone who personally partook in Kwanzaa celebrations, I didn’t give it much further thought after the end of those sweet, 22-minute animated instalments.

However, over a decade later, pre-Christmas preparations brought the cultural holiday to mind once again ‒ and I found that though relatively few in number, there really are those for whom Kwanzaa is an unmissable part of the festive calendar, right here in the United Kingdom.

If you’ve been as much in the dark as I have, enjoy this quick look into Kwanzaa today ‒ what it is, who it’s for and why it came about in the first place…

Is Kwanzaa just ‘Black Christmas’?

A common misconception of Kwanzaa is that it’s the ‘black version’ of Christmas, and exists as an afrocentric alternative to the Christian traditional celebration. However, Kwanzaa was introduced as a means of celebrating the African heritage in African-American culture ‒ not with the intention of replacing any other religious celebrations.

‘Whether you’re Hindu, Muslim, Christian, or not a follower of religion at all, you can celebrate Kwanzaa ‒ it’s a cultural celebration, not religious,’ Gorden Stewart, co-founder of High Wycombe-based community group Afrikan Heartbeat, explains.

What is it, then?

Kwanzaa is a seven-day recreation period from 26th December to 1st January during which people of African descent are encouraged to celebrate and give honour to the contributions of African people throughout history. Through seven different principles, named in Swahili, celebrants pay mind to a theme per day, culminating in a big community celebration in the final days.

- Umoja: Unity

“To strive for and maintain unity in the family, community, nation and race.”

- Kujichagulia: Self-determination

“To define ourselves, name ourselves, create for ourselves, and speak for ourselves.”

- Ujima: Collective Work and Responsibility

“To build and maintain our community together and make our brothers’ and sisters’ problems our problems and solve them together.”

- Ujamaa: Cooperative Economics

“To build and maintain our own stores, shops, and other businesses and to profit from them together.”

- Nia: Purpose

“To make our collective vocation the building and developing of our community in order to restore our people to their traditional greatness.”

- Kuumba: Creativity

“To do always as much as we can, in the way we can, in order to leave our community more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited it.”

- Imani: Faith

“To believe with all our heart in our people, our parents, our teachers, our leaders, and the righteousness and victory of our struggle.”

What’s the point of Kwanzaa?

Established in the mid-1960s by Dr Maulana Karenga, Kwanzaa came about during the rise of the Civil Rights and Black Power Movement; a time where black Americans were actively demanding that the systemic disadvantages against them be overturned, and racial equality be implemented.

In 2009, it was reported by University of Minnesota professor, Dr Keith Mayes, that between 500,000 and 2 million people in the United States actively observed Kwanzaa ‒ between one and two per cent of the population. With these numbers being relatively small, it has been considered that interest Kwanzaa had ‘levelled out’ throughout the 1990s, as the Black Power movement declined.

However, with the rise of Black Lives Matter and growing resistance to right-wing and fascist movements in the west, could the next few years see a renewed curiosity into the celebration of African diasporic culture?

How do you celebrate?

Much of the essential Kwanzaa celebration revolves around the lighting of seven candles, held in a kinara (candle holder), one-a-day until the end of the week. Each candle represents one of principles, and the corresponding principle will be discussed within the family.

A large feast (karamu) is held on December 31st, where extended families often come together to eat. In the US, the cuisine often takes inspiration from various African countries, as well as ‘soul food’. Gifts are presented to children from their parents; often consisting of a book and a ‘heritage symbol’, the presents instil the importance of learning and passing on knowledge in the younger generations.

The week of celebration ends on January 1st, with a day reserved for contemplation about the principles, and how they can be incorporated into their everyday lives throughout the upcoming year. According to Gorden Stewart: ‘If we continue these throughout the year, they’ll continue to uplift and guide us.’

Is it relevant for black people outside of America?

Though the majority of those who observe Kwanzaa celebrations reside in the US, in the 51 years since its initial celebrations, there have been groups who observe the period all over the world: from West African countries such as Ghana and Nigeria, the Caribbean, and indeed, in Britain.

Stewart tells us that its focus on honouring African heritage and reconnecting people to their ‘roots’ means that Kwanzaa can be relevant to across the African diaspora.

‘If you’re of African heritage, wherever we are in the world we have a cultural connection,’ he explains. ‘Whether it was Nelson Mandela being freed in South Africa, or seeing Muhammad Ali succeed in boxing, we all felt the same connection and celebrated together.

‘The problems faced by black people in America aren’t too different to what’s experienced here, or by people of African heritage in other countries. As black people in the UK, we’ve have our struggles with discrimination and injustice too, so there’s just as much relevance in celebrating African heritage, and uplifting ourselves here as there is in the States.’

How can I get involved?

Nowadays, where else would you get started on your research into Kwanzaa than the internet? Websites such as officialkwanzaawebsite.org provide more information on how to practice, as well as social media groups sharing information on local events to get involved with: Kwanzaa Network UK is one example, accessible through Facebook.

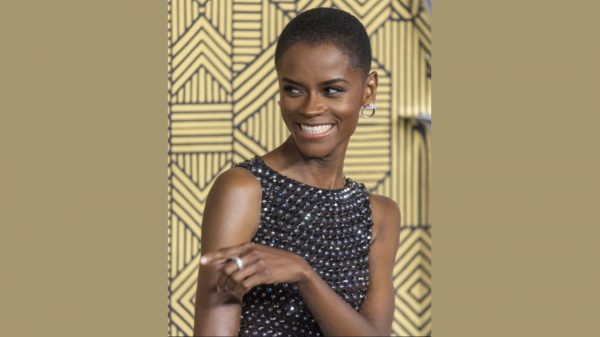

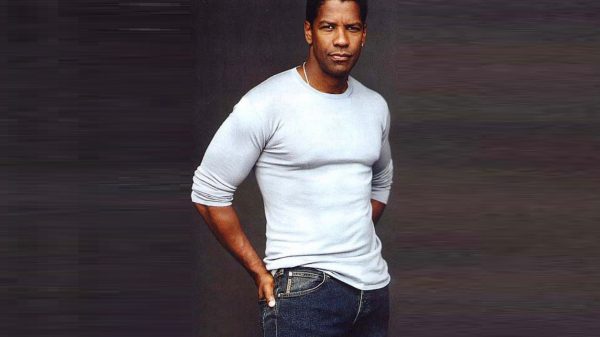

Each year, groups in London, Birmingham, Bristol, Wolverhampton and more organise events with presentations, dances, speeches and art in celebration. The 50th anniversary celebrations in East London back in 2016 was a well-attended affair, as evidenced in the kindly-provided photos throughout the article.

Though exact numbers of those who celebrate Kwanzaa in the UK are unknown as of yet, it’s clear that there is a community, and a market for it. Will you be a part of it this year?